So I was just thinking about the buoyant force and came up with what seemed like a simple perpetual motion based on it. Obviously such things are not physically possible so I'm trying to figure out where this machine goes wrong.

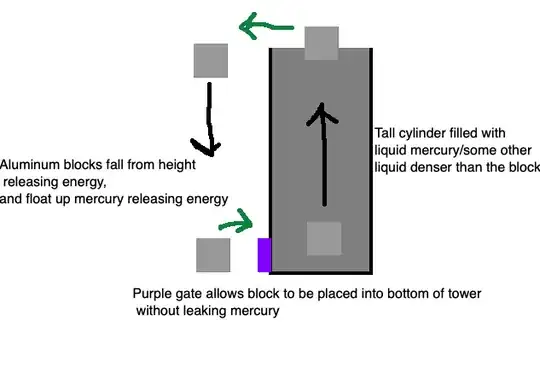

So, the schematic is to have a large tower consisting of some high density liquid (we use mercury in the example) and to have a block (i choose aluminum) which is denser than the ambient surrounding liquid (air) and less dense than the tower's liquid.

So, the principle of operation would be to get the block into the bottom of the tower via a gate which I can pretend is a selective membrane that only allows aluminum blocks in but no mercury out (some energy is spent pushing it through this membrane)

Once the block is inside it floats up doing work equal to $(m_\text{displaced_fluid} - m_\text{block})gh$ and at the top we then spend some energy to knock it off the top of the tower where the block now is in free fall and capable of doing work equal to $(m_\text{block})gh$

So analysis:

- Knocking the block off the top of the tower can be made to take a very small amount of energy (and or make the tower very tall) so it can't be the primary point of waste here.

Which leads us to conclude

- The "purple gate" our apparatus for pushing the block is not physical?

This requires some energy to push the block in i.e. $\text{volume}_{block} \times \text{fluid density}$ but if the tower is made sufficiently tall then that energy expense would be far less than what is generated when the block floats up. I find this hard to believe since selective membranes certainly can operate at the microscopic level (our cells use them all the time).

Third idea?

Is it somehow possible that the selective membrane is okay but the energy required to get the block through the membrane is proportional to the height of the tower? I could imagine its possible to estimate this if we assume the block displaces the fluid directly above it, which displaces the fluid above that etc etc etc meaning the amount of fluid displaced/moved is now proportional to the height of the tower. But I am no longer confident that analysis is correct.