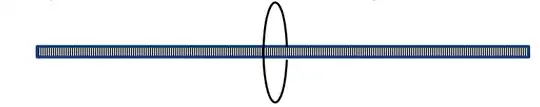

The formula you are referring to is only an approximation for very long solenoids. The magnetic field outside but close to the very long solenoid is very weak, so that only the magnetic field inside the solenoid contributes significantly to the EMF in the loop in this limit case:

$$\oint_{\partial A} \vec E\cdot d\vec s=\int_A (\nabla \times \vec E)\cdot d\vec A=-\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\int_A \vec B\cdot d\vec A\approx-\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\int_{A_{Solenoid}} \vec B\cdot d\vec A$$

which has indeed an amplitude independent of the loop radius, given for example a sinusoidal excitation of the solenoid.

The situation changes, if you widen the loop considerably. Then you will also capture part of the magnetic flux that returns outside the solenoid. If you finally let the loop tend to infinity, then the total magnetic flux through its cross section will tend to zero, and with it the induced EMF.

See this reference for a calculation of the solenoid field. Although this is still a short solenoid, it illustrates the basic observation that the magnetic flux density drops abruptly when crossing the boundary between inside and outside the solenoid. For the long solenoid it is going to be even more pronounced. By the way, the software used is FEMM, a free software I have also often used to understand electro-/magnetostatic problems. You could build a long solenoid yourself with it by only a small effort. However, the tool is limited to 2D problems, but the solenoid is one if you choose cylindrical coordinates.

On german Wikipedia there is also this graph, which even gives a better impression about the flux density jump when crossing the windings.