You know the strong force (the one that keeps quarks together). Well it works by exchanging gluons right? So how does that force keep the quarks together? I mean you can imagine that process as three people passing balls between them right? Well as far as I know that throwing of the ball wouldn't force those 3 persons to stay within a range. I had this one idea that when a gluon is emitted it results in a force that pushes the quark in the opposite direction but that would be towards the outside of the quark right? Pls explain this to me. Any help would be helpful and greatly appreciated.

5 Answers

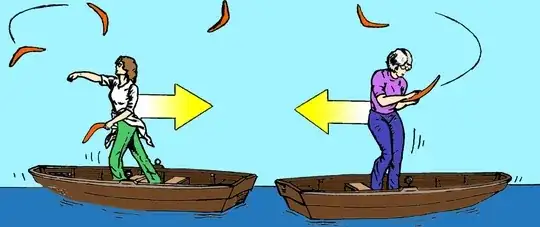

You have stumbled into one of the most interesting questions of QED and QCD, that is, how can we model the attractive and repulsive forces by the exchange of the massless mediators (photon and gluon respectively)? The answer is mathematically very complicated and when we look for an explanation in our everyday classical view, there is a very nice analogy:

These are very nice classical analogical explanations of how momentum conservation laws can be obeyed by the exchange of the mediator particles (in your case gluons). For repulsive forces, it is easier to understand by throwing balls at each other, but attractive forces are a little bit harder to understand classically, these boomerangs can give a nice analogy.

How can photons cause charges to attract?

All internal lines in a Feynman diagram are force carriers, i.e. transfer dp/dt by construction,not only the gauge bosons. See the diagram for compton scattering for example. Lattice QCD goes for direct solutions on the lattice, and therefore the concept of virtual particles is not necessary. It is a different calculational approach , although the article involves quark propagators in the calculations.

Are force carrying particles always virtual particles?

It is very important to understand that usually these are mediator exchanges are described using a mathematical model that uses virtual particles (like virtual photons), although in the case of lattice QCD virtual particles are not necessary.

- 30,008

Unfortunately, there is no nice answer.

The cop out answer is that the quantum world is weird and your picture of balls doesn’t really work at that level.

A slightly better answer is: the gluons exchanged are virtual, this means they don’t really exist which allows them to behave in ways which are classically forbidden.

- 2,045

The people-throwing-balls-at-each-other analogy doesn't really work. In quantum field theory, all interactions happen through particle exchange, but the situation really isn't at all similar to any analogy that I've ever heard in the classical mechanics. The explanation is in the math.

Particles interact with each other through a field (like the electromagnetic field or the gauge field), and when we apply the laws of quantum mechanics to a field, we find out that the energy of the field can only come in discrete chunks (quanta) which we associate with particles. For example, for the electromagnetic field, the associated particle is the photon, so electromagnetic interactions, mediated by the electromagnetic field, take place through the exchange of photons.

- 4,211

A simple reason why your ball-throwing-analogy is misleading, is that you cannot throw "virtual" balls, i.e. balls whose energy-momentum-relation is off. Furthermore, the "interaction points", where one particle sends off the exchange particle and the other catches it, are not localized.

When you go too far with the story about "exchange particles" it breaks down. I'd always rather think of the whole story as just a graphical representation off mathematical expressions. There is too much going on in QFT, especially in QCD where you wouldn't even find free elementary particles due to confinement.

The problem is that our classical intuition is simply wrong at that level, so it is futile to try to construct quasi-classical interpretations, imho.

- 306

- 1

- 4

The 'throwing balls at each other' analogy gives a really clear picture for a repulsive forces, but not for attractive forces. I've seen attempts with boomerangs and not-letting-go, but basically it doesn't work. I suspect that, even though it's often seen when popularising QED and other forces, we would be better off not using it. Sorry. But it's more confusing than helpful.

Let me offer - cautiously - an alternative which is not totally satisfactory but probably better than falling back on "It's all in the theoretical quantum stuff".

Between particles there is a field which is some function of the displacement between them. That function can be expanded as a Fourier transform - that's just basic mathematics. That's visualisable as sine/cosine standing waves.

Now a standing wave can be expressed as the sum of two travelling waves. $cos(kx)e^{i\omega t}=(e^{i(kx+\omega t)}+e^{i(-kx+\omega t)})/2$. If one particle absorbs one of the travelling waves, and the other particle absorbs the other, then each particle gets some momentum. These impulses are equal and opposite, and can be attractive or repulsive depending on which particle absorbs which wave.

- 10,293

- 1

- 22

- 45