I initially suspected that the picture here is one of a sand bar next to deeper water, not of two "seas" not mixing, where the light-colored water is light because it is shallow, and we are seeing the sand below, and the dense region is dark because it is too deep to see the bottom, and the light is absorbed rather than reflecting back.The foam we see at the border is from waves that are pushed up when the deep-water waves encounter suddenly shallower water. I think, having read another response (see comment below; I can't remember the name of the author ATM and the edit section doesn't allow me to see it) that he's right: it's one liquid (say, a large river of fresh water) flowing into another (probably the ocean or something connected to it).

You're right that different-density liquids will eventually mix if they are mutually soluble, but generally, when you have a case of two mutually soluble liquids with different densities, they're top & bottom, rather than side-by-side.

You can get this effect at home with water, sugar, and food coloring. First, mix 2 parts sugar with one part water. Heat until all of the sugar is dissolved, and add some blue food coloring. Put it in a clear container. Allow it to cool to room temperature.

Next, mix some red food coloring with water. Pour it over the back of a spoon slowly and gently so as to minimize mixing.

The glass should show blue on the bottom, red on top, with minimal purple in the middle if you can do it right. It should persist for at least a few hours, possibly a few days. This is similar to what happens in the global conveyor belt, where cold, dense, saltier water is beneath warm, relatively less saline water. It can also happen on a smaller scale, with brinicles, as explained by Alec Baldwin.

Your

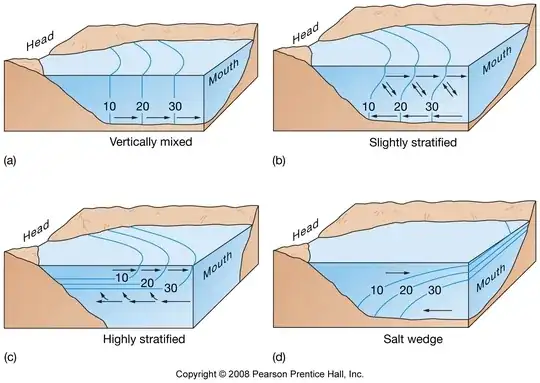

picture is an example of so called salt wedge estuaries. The classical

example of such wedge is

Your

picture is an example of so called salt wedge estuaries. The classical

example of such wedge is