Rody and Mike almost got it right. :)

Most aircraft are designed with swept wings. That is the primary mechanism that gives the roll effect to an airplane that may only receive a yaw input. if you look at this picture:

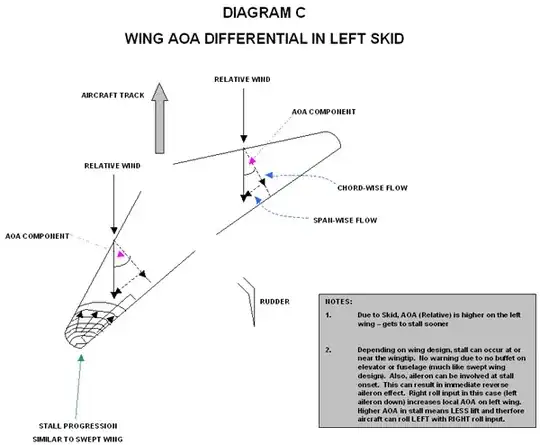

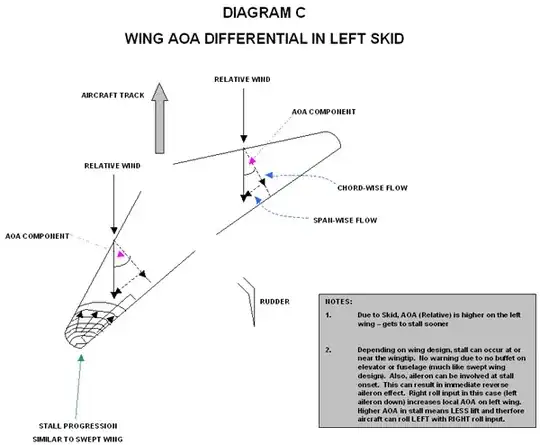

You can see that both wings have a backwards sweep to them. Now, if you introduce a yaw to the aircraft, one wing will extend out more directly into the wind-stream, while the other wing will be even more swept. This effectively makes one wing longer, and the other wing shorter. Like in this image (this image is actually displaying a more extreme case that also involves boundary layer separations, but that is beyond this answer):

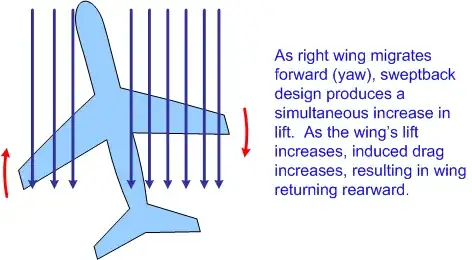

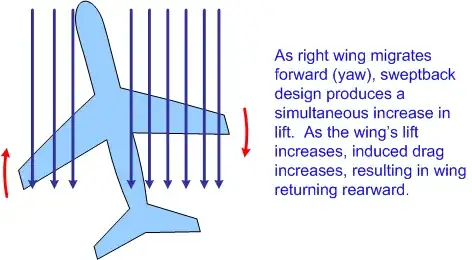

Actually, this picture displays it exactly as I was taught in USAF flight school::

The longer wing will generate more lift, and the shorter one will generate less lift. And since there is unequal lift around the roll axis, the airplane will roll, and continue to roll.

Of course, with more lift comes more drag, so that will counter the lift and pull the wing back (Causing an effect known as "Dutch Roll"). Many aircraft have a device called a "yaw damper" to counter this (or else you will feel quite queasy flying). Dutch roll is demonstrated by this GIF:

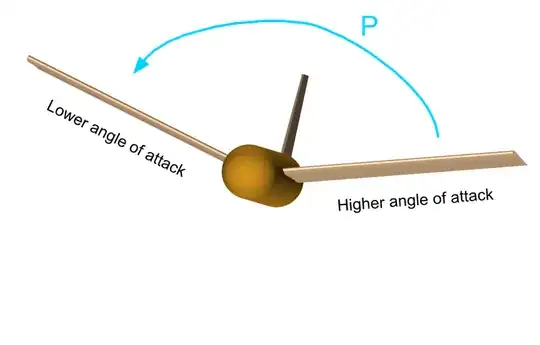

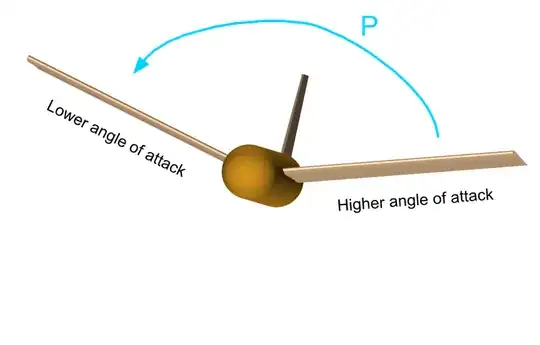

The reason that Mike's answer is not totally correct is from Figure 2 in his wiki link. Note that the words "non-zero" are included in this diagram:

That means that theoretically, if one were able to yaw an aircraft with dihedral perfectly, the aerodynamic forces would not be the causal factor. Also, most aircraft that have a dihedral or anahedral configuration also have a wing sweep, so that is the overall factor that is at play.