According to sources online (eg HyperPhysics) the electric field strength around a point charge is $$E=k\frac{Q}{r^2}$$ This must means that the further you get away, the electric field should decrease with the square of the radius right?

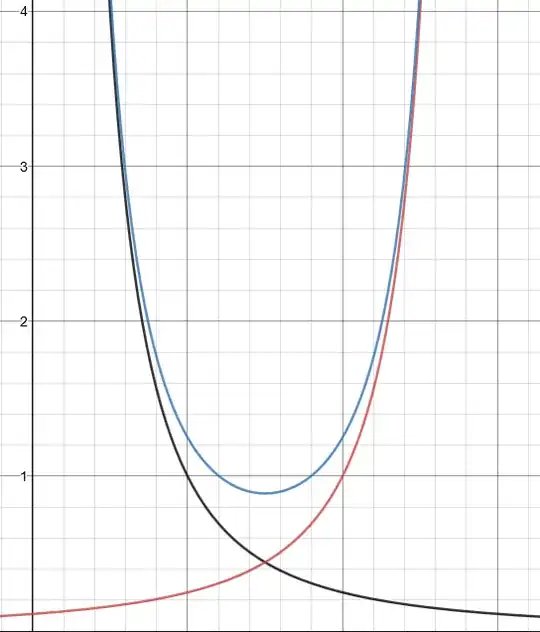

But when these charges are placed into parallel plates somehow these will produce a uniform electric field? How I currently understand the physics can be summarized in the graph below of the electric field strength vs distance (Red and black lines are the electric field strengths of each plate and the blue is the resultant).

It seems pretty clear this wouldn't be a uniform electric field. What happens such that the electric field strength is changed into a uniform field? I initially thought integration, but wouldn't that still give an inverse relationship?

In response to the proposed duplicate, my question is concerning 2 plates where as the other is about one plate (however, I can't really decipher what is being asked in the other question)