The uniqueness of the steady-state solution $\rho_{ss}$ satisfying $\mathcal{L}\rho_{ss} = 0$ depends on certain properties of the Liouvillian superoperator $\mathcal{L}$.

1- When the Liouvillian is irreducible:

An irreducible Liouvillian means that the dynamics cannot be decomposed into independent subspaces. Mathematically, this implies that there is no non-trivial subspace of the system's Hilbert space that is invariant under both the Hamiltonian $H$ and all Lindblad operators $A_i$ (if there are multiple).

Irreducibility means that the dynamics connect all states in the Hilbert space. For enough time, the system can evolve from any initial state to any other state and ensure convergence to a unique steady-state. The uniqueness of the steady-state for irreducible Liouvillians is a result of the Perron-Frobenius theorem.more

In an irreducible system, the dynamics mix all parts of the Hilbert

space, so no matter where you start, the system eventually forgets its

initial state and converges to a unique steady-state.

- Example of Unique Steady State With Irreducibility

A qubit with a jump operator $A = \sigma_-$ representing spontaneous decay from the excited state $|1\rangle$ to the ground state $|0\rangle$.

$$

\mathcal{L}\rho = \sigma_- \rho \sigma_+ - \frac{1}{2}\{\sigma_+ \sigma_-, \rho\}.

$$

$\sigma_-$ connects $|1\rangle \to |0\rangle$, ensuring no subspace is left.

While irreducibility guarantees uniqueness, the converse is not always true.

A system can have a unique steady-state without being irreducible. This could happen, for example, if the steady-state is common to ** multiple subspaces** or if all initial states are driven to a single point.

- Example of Unique Steady State Without Irreducibility

Consider atwo-qubit system where each qubit evolves independently under spontaneous emission (the qubits are not interacting). The system has two Lindblad operators: $A_1 = \sigma_-^{(1)}$ (affecting qubit 1) and $A_2 = \sigma_-^{(2)}$ (affecting qubit 2). Assume no interaction Hamiltonian, so $H = 0$.

$$

\mathcal{L}\rho = A_1 \rho A_1^\dagger + A_2 \rho A_2^\dagger - \frac{1}{2} \left\{A_1^\dagger A_1 + A_2^\dagger A_2, \rho \right\}.

$$

Each qubit independently relax to its ground state because of spontaneous emission. The dynamics of qubit 1 are independent of qubit 2, so the system is reducible to two subspaces(for each qubit one subspace).

Inspite of having reducible system, both qubits eventually relax to the ground state $|0\rangle^{(1)} \otimes |0\rangle^{(2)}$, lead to the unique steady state

$$

\rho_{\text{ss}} = |00\rangle \langle 00|.

$$

Thus, the system is reducible but still converges to a unique steady state because all the subspaces evolve to the same steady state.

2- When the system is ergodic:

Ergodicity implies that the long-time average of any observable converges to the same value regardless of the initial state. Ergodicity is often a consequence of irreducibility. Ergodicity implies that the system's long-term time averages (example of an observable) converge to the same value regardless of the initial conditions.

Point: Classical ergodicity is about visiting every point in phase space, while in quantum systems, ergodicity refers to the entire Hilbert space being explored due to dissipative dynamics.

3- When there are no conserved quantities:

If there are no observables (apart from the identity operator) that commute with both the Hamiltonian $H$ and all Lindblad operators $A_i$, the steady-state is in most cases unique.

4- When the Liouvillian has a non-zero spectral gap:

If there is a gap between the zero eigenvalue (corresponding to the steady-state) and the next eigenvalue of $\mathcal{L}$ in the complex plane, the steady-state is unique. The size of the spectral gap also controls the rate of convergence to the steady-state. Larger gap, faster convergence.

Point: If the Liouvillian has a degenerate zero eigenvalue, this leads to multiple steady states.

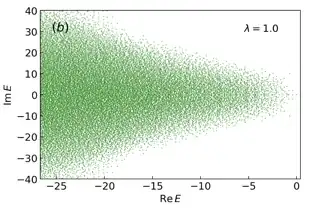

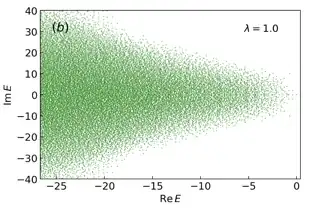

Fig. Scatter plot of the complex spectrum of the Liouvillian L of the dissipative Dicke model. The unique steady-state of the

dynamics corresponds to the single eigenvalue located at

$E=0$. source

Above answer was my attempt to explain the properties I have in mind. If there are additional relevant properties or a better way to categorize them, please let me know in comments so I can make this answer more complete and helpful.