What is the connection between special and general relativity? As I understand general relativity does not need the assumption on speed of light constant. It is about the relation between mass and spacetime and gravity. Can general relativity be valid without special relativity?

7 Answers

Suppose we start by considering Galilean transformations, that is transformations between observers moving at different speeds where the speeds are well below the speed of light. Different observers will disagree about the speeds of objects, but there are some things they will agree on. Specifically, they will agree on the sizes of objects.

Suppose I have a metal rod that in my coordinate system has one end at the point $(0,0,0)$ and the other end at the point $(dx,dy,dz)$. The length of this rod can be calculated using Pythagoras' theorem:

$$ ds^2 = dx^2 + dy^2 + dz^2 \tag{1} $$

Now you may be moving relative to me, so we won't agree about the position and velocity of the rod, but we'll both agree on the length because, well, it's a chunk of metal - it doesn't change in size just because you are moving relative to me. So the length of the rod, $ds$, is an invariant i.e. it is something that all observers will agree on.

OK, let's move onto Special Relativity. What Special Relativity does is treat space and time together so the distance between two points has to take the time difference between the points into account as well. So our equation (1) is modified to include time and it becomes:

$$ ds^2 = -c^2dt^2 + dx^2 + dy^2 + dz^2 \tag{2} $$

Note that our new equation for the length $ds$ now includes time, but the time has a minus sign. We also multiply the time by a constant with the dimensions of a velocity to convert the time into a length. Just as before the quantity $ds$ is an invariant i.e. all observers agree on it no matter how they are moving relative to each other. In fact we give this spacetime length a special name - we call it the proper length (or sometimes the proper time).

By now you're probably wondering what on Earth I'm rambling about, but it turns out we can derive all the weird stuff in Special Relativity simply from the requirement that $ds$ be an invariant. If you're interested I go through this in How do I derive the Lorentz contraction from the invariant interval?.

In fact the equation for $ds$ is so important in Special Relativity that it has its own name. It's called the Minkowski metric. And we can use this Minkowski metric to show that the speed of light must be the same for all observers. I do this in my answer to Special Relativity Second Postulate.

So where we've got to is that the fact the speed of light is constant in SR is equivalent to the statement that the Minkowski metric determines an invariant quantity. What General Relativity does is to generalise the Minkowski metric, equation (2). Suppose we rewrite equation (2) as:

$$ ds^2 = \sum_{\mu=0}^3 \sum_{\nu=0}^3 \,g_{\mu\nu}dx^\mu dx^\nu $$

where we are using the notation $dt=dx^0$, $dx=dx^1$, $dy=dx^2$ and $dz=dx^3$, and $g$ is the matrix:

$$g=\left(\begin{matrix} -c^2 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{matrix}\right)$$

This matrix $g$ is called the metric tensor. Specifically the matrix I've written above is the metric tensor for flat spacetime i.e. Minkowski spacetime.

In General Relativity this matrix can have different values for its entries, and indeed those elements can be functions of position rather than constants. For example the spacetime around a static uncharged black hole has a metric tensor called the Schwarzschild metric:

$$g=\left(\begin{matrix} -c^2(1-\frac{r_s}{r}) & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{1-\frac{r_s}{r}} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & r^2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & r^2\sin^2\theta \end{matrix}\right)$$

(I mention this mostly for decoration - understanding how to work with the Schwarzschild metric needs you to do a course on GR)

In GR the metric $g$ is related to the distribution of matter and energy, and it is obtained by solving the Einstein equations (which is not a task for the faint hearted :-). The Minkowski metric is the solution we get when there is no matter or energy present${}^1$.

The point I'm getting at is that there is a simple sequence that takes use from everyday Newtonian mechanics to General Relativity. The first equation I wrote down, equation (1) i.e. Pythagoras' theorem, is also a metric - it's the metric for flat 3D space. Extending it to spacetime, equation (2), moves us on to Special Relativity, and extending equation (2) to a more general form for the metric tensor moves us on to general relativity. So Special Relativity is a subset of General Relativity, and Newtonian mechanics is a subset of Special Relativity.

To end let's return to that question of the speed of light. The speed of light is constant in SR so is it constant in GR? And the answer is, well, sort of. I go through this in some detail in GR. Einstein's 1911 Paper: On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light but you may find this a bit hard going. So I'll simply say that in GR the speed of light is always locally constant. That is, if I measure the speed of light at my location I will always get the result $c$. And if you measure the speed of light at your location you'll also get the result $c$. But, if I measure the speed of light at your location, and vice versa, we will in general not get the result $c$.

${}^1$ actually there are lots of solutions when no matter or energy is present. These are the vacuum solutions. The Minkowski metric is the solution with the lowest ADM energy.

- 367,598

Special relativity is the "special case" of general relativity where spacetime is flat. The speed of light is essential to both.

- 7,882

The best connection between the two theories regards how they deal with different observers or frames of reference. Special Relativity (SR) postulates that all inertial observers are equivalent whereas General Relativity (GR) assumes that a wider class of observers are equivalent. More precisely, all non rotating frames are equivalent. Thus, GR is more general than SR (aka Restricted Relativity) and therefore cannot be valid without SR. In another words, as theories, GR implies SR but the converse is not true.

- 18,168

I like to think of special relativity as first order or "local" general relativity.

One of the fundamental things underlying all relativity is the equivalence principle. But it kind of "disappears" in the mechanics, procedures and theory of general relativity. It is actually encoded in the "choice of building materials" for GR. That is, we think of spacetime as a manifold as opposed to other mathematical objects we might postulate it to be (such as a Variety - this is a somewhat silly example, because it's "almost" a manifold, but it is simple and meant to show that it is not a done deal that we must choose a manifold - there is real, in-principle-measurable physics affected by the choice). A manifold is a mathematical object that is everywhere locally Euclidean, or, in the case of GR, Minkowski. If we "zoom in" to the manifold at high enough magnification, we can make spacetime as near as we like to flat, Minkowski spacetime. More formally what this means is that we can always define a tangent space to every point. Here's the key to this answer:

As long as we don't go too far from this spacetime point and keep within a small neighborhood (it might have to be very small in highly curved space, but this is a theoretical possibility and our magnification can be any finite value), all relativistic calculations can be done with special relativity with the tangent space approximating spacetime in the neighborhood.

Inertial frames at the point in question are those momentarily comoving with objects and frames undergoing geodesic, torque-free motion in the more general, curved General Relativistic manifold and all of these are equivalent modulo a Lorentz transformation, just as in special relativity. Curvature is a second order notion, not definable in terms of the tangent space to one point alone. Einstein's original conception of the equivalence principle was that, to first order, there is no difference between experimental results carried out within a lab accelerated relative to these inertial frames defined by the tangent space. Whether they be accelerated by a rocket, or accelerated because the laboratory has bumped into and thus stuck to the surface of a planet, one cannot tell unless one looks outside the laboratory.

- 90,184

- 7

- 198

- 428

The essential, constituive point of the general theory of relativity is, as expressed by Einstein in his paper on "The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity" (1916), that:

The connection between the special and the general theory of relativity is consequently, that all notions of the special theory which relate to space-time (incl. geometric and kinematic relations between material points) are explicitly defined in terms of (determinations of) space-time coincidence;

namely foremost the notions appearing in the "postulates of special relativity" (1905):

"coordinate systems in uniform translational motion relative to each other"

(i.e. in modern, coordinate-free terminology "inertial frames"), and"velocity" (along with the related notions "speed", "distance", and "duration").

Can general relativity be valid without special relativity?

In the above sense, SR is manifestly a special case of GR.

It is about the relation between mass and spacetime and gravity[?]

Definitions of (how to measure) "mass" and all more or less related dynamic quantities (momentum, energy, angular momentum, charges, field strengths ...) are based on (and therefore subsequent to) the geometric and kinematic space-time verifications.

- 4,360

There is already a nice answer by John Rennie. So I am trying to answer the question in a different way, focusing mainly on the transition from Newtonian viewpoints to general relativity.

Let’s start with a simple example of the Earth-Sun system. According to Newton, the earth wants to move inertially, i.e., uniformly in a straight line. A gravitational force from the sun deflects it and causes it to move in an elliptical orbit around the sun.

However, according to GR, the presence of the sun disturbs (curves), the fabric of space and time. The earth then merely moves inertially in this new disturbed spacetime. It follows an inertial trajectory, but that trajectory has been distorted so that it ends up as an ellipse in the space around the sun, or more precisely, a helical trajectory winding around the sun's worldline in spacetime.

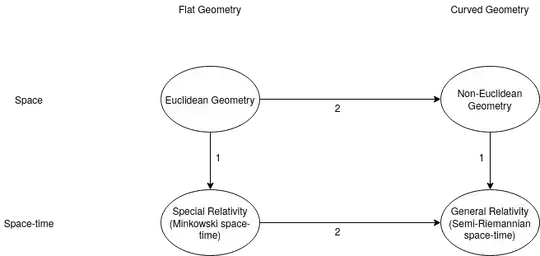

General Relativity is basically an unification of the following two major theoretical transitions:

- Transition from ‘space’ to ‘space-time’: The trajectories of bodies in inertial motion are straight lines in spacetime in the sense that they are curves of greatest proper time, that is, time-like geodesics. That makes them the analogs of the straight lines of Euclidean geometry, which are also called geodesics, the curves of shortest distance.

- Transition from ‘flat’ to ‘curved’ geometry: In the context of ordinary spatial geometry, this transition takes us from Euclidean geometry to non-Euclidean geometry. In the context of space-time theories, the same transition takes us from the geometry of a flat space-time (Minkowski space-time of special relativity) to the geometry of the curved space-time (semi-Riemannian space-time of general relativity). The central idea of Einstein's general theory of relativity is that this curvature of spacetime is what we traditionally know as gravitation.

These two transitions are the central ideas of GR, and the mathematics needed to develop the theory is just the mathematics of curved geometry, the only difference is that it is transported from space to space-time.

The following figure shows the two transitions:

One can summarize as follows:

General Relativity is a theory of gravity and a set of physical and geometric principles obtained from Newtonian gravity through a transition from the concept of ‘space’ to ‘space-time’ and the transition from flat geometry to curved geometry, which lead to a set of field equations that determine the gravitational field, and to the geodesic equations that describe light propagation and the motion of particles on the background.

- 2,085

- 15

- 27

The connection between SR and GR is more murky than it might at first appear:

Historical background

1905: Electrodynamics

Einstein's 1905 "On the electrodynamics of moving bodies" was essentially a rederived version of the relationships that made up the "skeleton" of Lorentz aether theory, but stripped of any aether-theory concepts. If the restricted principle of relativity applied to matter and light, and the lightbeam geometry defined for empty space still applied when a region was populated, then these were the relativistic relationships that HAD to hold.

Einstein followed this up with a paper deriving E=mc^2 from the LET-SR relationships. He "forgot" to mention that this was also an exact result of the earlier Newtonian relationships ... but he was in "promotional" mode.

1909: Minkowski spacetime

Einstein's fortunes changed in 1908/1909 with a couple of papers by Minkowski, which basically said that he, Minkowski, was the only person who properly understood the Lorentz-Einstein relationships, but that perhaps Einstein was #2. Minkowski then immediately died (1909), leaving Einstein the heir apparent, at which point Einstein finally managed to get a professorship.

1911: Gravity

Einstein calculates the "Newtonian" gravity-shift and the "Newtonian" bending of starlight by the Sun. He realises that gravity represents a warpage of lightbeam geometry, and that his earlier principle of the constant global velocity of light is wrong. However, the 1905 theory can still hold for gravitational plateaus, and over infinitesimally-small regions of spacetime.

1913: The GR project

When Einstein started his GR project in 1913, the aim was to generalise the results that he'd gotten for perfectly flat spacetime to problems involving gravity and the relativity of inertia. He'd already made a start on some of these problems, for instance with his famous gravity-shift paper of 1911. It was around this time (1913) that he started talking about "special-case" and "generalised" relativity, the idea being that the 1905 theory would be an exact limiting case of the new system.

The new system (he later wrote), was like a building with two stories: Special relativity provided the foundation, describing all physics except gravitational physics, and deciding the fundamental equations of motion, after which a GR layer dealt with the additional physics required for gravity.

1915/1916: General Relativity

Einstein was forced to announce a finalised version of the theory in very late 1915 in order to avoid a possible priority dispute, and published the new theory in early 1916.

Almost immediately, he realised that the new theory didn't work as specified, specifically, if failed to implement the relativity of inertia.

1917: Revisions

Einstein modifies the space of GR1916 from infinite and pseudo-Euclidean, to finite and hyperspherical, in order to try to get the relativity on inertia to work. It still arguably doesn't. Also, the new version makes gravitational curvature cumulative and shifts path-dependent, whereas the SR/Schwarzschild equations require curvature to be non-cumulative. To prevent the SR relationships being overturned, Einstein invents Lambda, the Cosmological Constant, whose purpose is to exactly cancel out long-distance cumulative curvature effects. Lambda comes to be seen as a mistake, and gets set to zero. This puts Hubble cosmology at odds with SR and SR-based-GR.

1921: Princeton Lectures

Einstein explains how general relativity at least partially implements Mach's principle in the form of gravitomagnetic effects.

1924: Rejecting Mach

Einstein gives up on Mach's principle, and re-brands GR as being based on the Principle of Covariance, saying that if a theory satisfies the PoC it automatically satisfies the GPoR. This turns out to be wrong.

1950: GR without SR? GR mkII ?

Einstein returns to GR, saying that he now considers it wrong to add components to a general theory unless they are known to be compatible with the GPoR (SR wasn't certified GPoR-compatible). He no longer considers the "SR plus GR" two-layer architecture of GR1916 to be defensible. He no longer considers it to be legitimate to ask: "What would physics look like without gravitation?". His argument for a "reboot" of GR seems to involve rejecting special relativity.

1952: The Moeller disproof of GR1916

Moeller's book on general relativity proves that an SR-based system of physics cannot support gravitomagnetism. As acceleration can be broken down into constituent velocity stages, accelerative GM curvature is the aggregate of the smaller component velocity-dependent curvatures. With the SR equations there are no velocity-dependent curvatures, therefore also no rotational and accelerative curvatures, making acceleration and rotation absolute, not relative. The accelerated or rotating observer sees curvature effects due to their curved path through flat spacetime, but the effect is not symmetrical or mutual. This observation destroys Einstein's SR-based 1916 attempt at a general theory. We can have either SR or gravitomagnetism and the GPoR, but not both.

The 1960 Crisis

The community realises that the principle of equivalence of inertia and gravitation also cannot coexist with SR (in rotation problems), as two parts of a larger theory (Schild). Once again, we have a choice between SR and the GPoR, and cannot have both. Schild states that if we're forced to make a choice, then since SR is the more solid theory, our position must be to back SR and downgrade GR to an approximate, heuristically-useful idea that can be overridden by SR. This is not too different to Einstein's 1913 characterisation.

Analysis

Einstein's 1950 assessment is correct: although the 1916 theory makes GR reduce to SR by definition, these are in fact two different and incompatible systems, making Einstein's 1916 definitions geometrically impossible to implement. Special relativity only works if there is never any gravitomagnetic dragging effect associated with moving matter, GR only works if there are always gravitomagnetic dragging effects associated with moving matter. These are two mutually exclusive criteria ... "never" is not a subset of "always", and SR cannot be a legal physical subset of a valid general theory. SR is sometimes characterised as modelling inertial mass "with gravity switched off". According to the PoE, one can never "switch off" gravity without also "switching off" inertia, so SR violates the PoE. SR is inertial physics in flat spacetime, but in the context of a general theory, all massed particles have associated curvature, meaning that there is no such thing as "inertial physics in flat spacetime" for GR to reduce to. A general theory of relativity needs to be self-contained and free-standing, not based on some other system whose principles aren't compatible with it.

Reduction to SR

The supposed geometrical reduction of curved-spacetime physics to flat-spacetime physics is a classic bit of misdirection, as it only works in the absence of matter. Yes, if we take a classically-curved surface and zoom in in it, it becomes an arbitrarily-close approximation of a flat region, with flat tangent-spaces mapping to the real metric arbitrarily closely.

But this only works if a region is empty, and contains no particles to watch, and no physical observers to watch them. If a region contains field-sources, and we accidentally select the location of a field-source to zoom in on, the curvature in our field of view increases as we zoom, rather than decreasing.

General relativity allows us to select regions between particles to zoom in on and obtain SR, but we cannot zoom in on regions that contain particles and get the same outcome. So SR's legitimacy as a theory of inertial physics and subset of curved-spacetime physics, is limited at best to regions that contain no matter. And if there are no observer-masses in a region, then the region contains no "observations" that need "relativising", and the application of the PoR becomes moot. SR within GR is a null theory.

Summing up, general relativity can be considered as supporting two different classes of nominal observer, real, physical observer-masses whose presence and motions warp spacetime, and unphysical, purely-mathematical hypothetical observers whose presence and motion has zero effect on spacetime.

The relativity of the second class of observer gives us SR, but it is the relativity of the first, physical class of observer that gives us GR's inertial physics. Since the geometries and behaviours and properties of the two classes are different, then although GR might be said to contain SR as a solution, it's an unphysical solution. GR's legitimate inertial physics is given by the other solution, and the other set of equations and laws.

It's this careless failure to distinguish between "physical" and "unphysical" solutions that has made general relativity such a mess for the past hundred-odd years.

A resource that I've compiled of linked sources and quotes used (119 refs): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386508459_Problems_with_Einstein's_general_theory_of_relativity

- 138