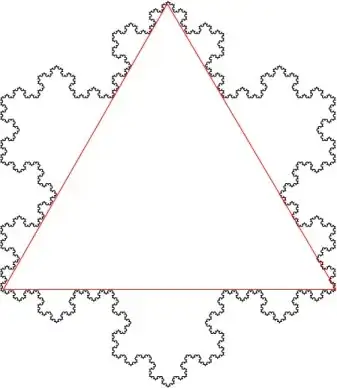

Here are a few observations about this problem:

1) You mention that an infinite amount of charge would be needed by the $\infty$-th iteration, but this is not so. By holding the amount of charge in the system constant, the linear charge density of the shape can easily be determined to be

$$

\lambda_n=\frac{3^{n-1}Q}{4^nL}

$$

where $Q$ is the total charge and $L$ is the length of one side of the initial equilateral triangle. This means that the linear charge density of the $0$-th iteration (the triangle) is $\frac{Q}{3L}$ as expected.

2) However, your observation that the problem becomes invalid in the fractal limit (at the $\infty$-th iteration) is correct. It becomes invalid not due to an infinite amount of charge but because the curve is no longer integrable. A fractal has an uncountable number of discontinuities and is therefore not differentiable - which is a requirement for computing the integral that determines the field of this shape.

3) That integral for the electrostatic potential can be stated quite briefly as

$$

\phi(\vec x)=k \lambda_n\int_{C}\frac{dl}{|\vec x -\vec x_0|}

$$

where $\phi (\vec x)$ is the electrostatic potential at point $\vec x$ in space, $k$ is Coulomb's Constant, $\lambda_n$ is the charge density defined above, $C$ is the curve defined by the perimeter of the Koch Snowflake, $dl$ is the infinitesimal length along $C$, and $\vec x_0$ is the location in space of that infinitesimal length.

Long story short, you can parameterize the curve (and therefore $dl$) over $\vec x_0$ and take the integral. Because of the symmetry, you'd only need to complete the integral for one side of the snowflake and then multiply by 3. This process is possible (albeit cumbersome and tedious) for all finite n; however, taking the limit will fail since the curve has no infinitesimal smoothness.

That said, with enough time, you could write a computer program that correctly paramaterizes the curve and computes the integral for any value of n. If you did this (which is by no means a trivial task), you ought to find that the integral's result for higher and higher values of n slowly converges. So, in a way, you can determine the limit through numerical approximation, but this process would be very challenging and has no corresponding functional limit.

4) A similar argument can be made for your reframed question. All you would do is construct a surface charge density and do a 2-dimensional integral over the area of the shape. This integral is no easier than the other one, but I would expect it to also slowly converge.