There is a blog post by Matt Strassler about the structure of hadrons.

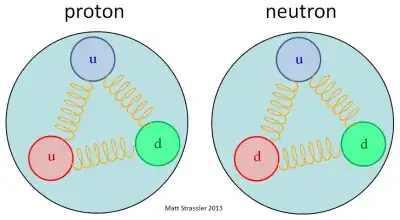

He contrasts the "conventional" picture of hadrons shown below:

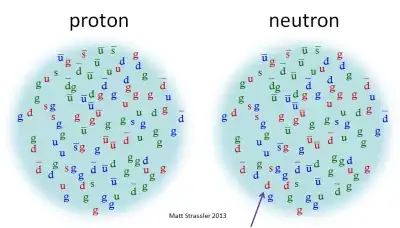

with one that he considers to be more accurate:

From the second figure, one would be led to believe that there is no such thing as a "valence quark", and that the only reason we say that a proton contains two up quarks and one down quark is that (up quarks - up antiquarks) = 2 and (down quarks - down antiquarks) = 1.

Unfortunately, it appears that such a model cannot explain the difference between a glueball and a flavourless meson of equal spin. Both would simply be a fuzzy cloud of quarks and antiquarks in equal number, together with some gluons. How could we decide which one is a glueball and which one is a meson?

Do we understand the actual state of the quark and gluon fields inside a hadron well enough to give a criterion based on the field configuration that distinguishes mesons from glueballs? Or is that distinction purely based on experimental data? (i.e., when this particle collides with other particles it "behaves" as though there are 2 quarks inside it)