At xmas, I had a cup of tea with some debris at the bottom from the leaves. With less than an inch of tea left, I'd shake the cup to get a little vortex going, then stop shaking and watch it spin. At first, the particles were dispersed fairly evenly throughout the liquid, but as time went on (and the vortex slowed, although I don't know if it's relevant) the particles would collect in the middle, until, by the time the liquid appeared to almost no longer be turning, all the little bits were collected in this nice neat pile in the center.

What's the physical explanation of the accumulation of particles in the middle?

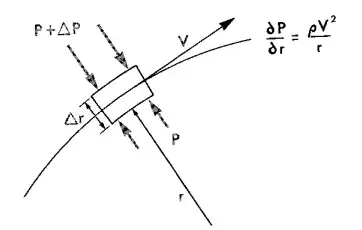

My guess is that it's something to do with a larger radius costing the particles more work through friction...