I'll sketch one of the eternal inflation variants: "false-vacuum driven eternal inflation".

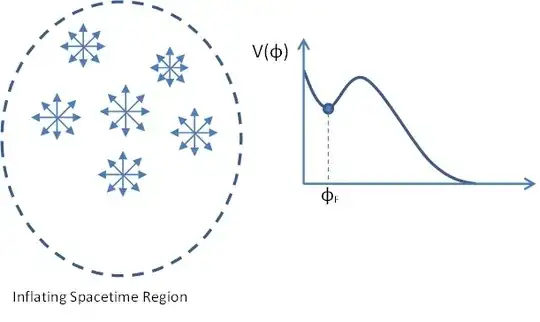

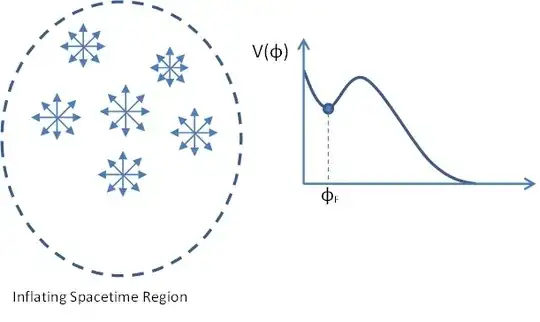

The idea is that you start with a spacetime manifold, on which is everywhere defined some scalar field. The scalar field ensures that whole region undergoes inflation. To ensure some sort of stability, the value of the field is chosen to be at a local minimum of the potential - it's not at the global minimum and hence tends to be called a false vacuum.

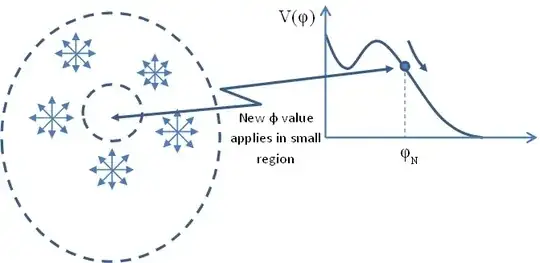

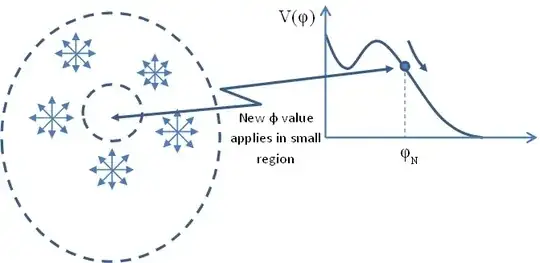

Now, due to some sort of perturbation, or due to quantum mechanical tunneling, the scalar field ends up, at least at some location, having a value at the other side of the potential barrier. One tunneling mechanism is described by the Coleman de Luccia instanton. This point with the new tunneled-to $\phi$ value is thought of as the origination point of a small bubble containing a different phase inside the inflating spacetime. It's sometimes called a nucleation point in analogy with bubble nucleation, in which bubbles form on particles suspended in a liquid.

The potential is now able to roll down the hill and release energy inside the bubble. The bubble wall expands and the bubble contents continue to expand, but at an ever decreasing rate. Anything inside this bubble, i.e. in the forward light cone of the nucleation point has the new $\phi$ value, and hence physics in there sees a different vacuum. The spacetime inside this bubble has a "natural" foliation by 3-dimenional hypersurfaces of constant $\phi$. As $\phi$ decreases, these surfaces become spatially flat, like our observable universe.

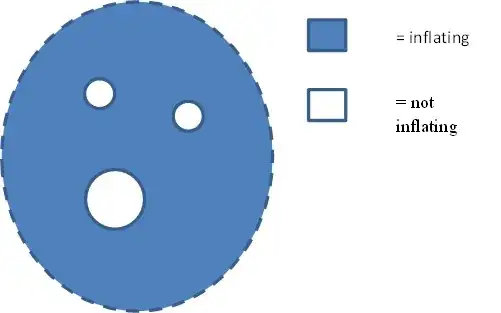

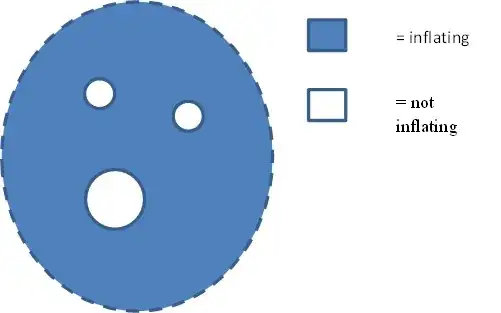

These bubbles ("pocket universes") originate in regions where inflation actually ends. So in this soft of model, the orgin of our observed universe, is the end of inflation. Outside of the bubble in question, other bubbles are continually nucleating. Bubbles may even merge.

Of course this sort of model is only as good as the predictions it makes for our observable universe. There has been some discussion of the possible observability of bubble nucleation in our past. See here for example.

So, getting back to the question, if you want to attach the term "multiverse" to this scenario, I would assume it refers to the ensemble of pocket universes, embedded in an inflating false vacuum spacetime which, at least in this toy model, obeys the usual laws of GR and quantum mechanics.