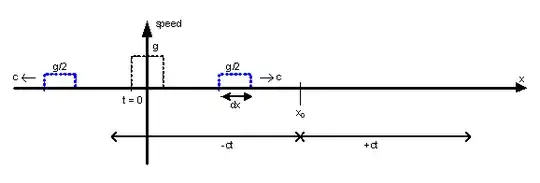

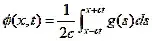

If $\phi(t,x)$ is a solution to the one dimensional wave equation and if the initial conditions $\phi(0,x)$ and $\phi_t(0,x)$ are given, then d'Alembert's Formula gives

$$\phi(t,x)= \frac 12[ \phi(0,x-ct)+ \phi(0,x+ct) ]+ \frac1{2c} \int_{x-ct}^{x+ct} \phi_t(0,y)dy . \tag{1}$$

Letting $g(x)=\phi(0,x)$ and $h(x)= \phi_t(0,x)$ (with $c=1$, so $ct=t$) this is commonly written

$$\phi(t,x)= \frac 12[ g(x-t)+ g(x+t) ]+ \frac12 \int_{x-t}^{x+t} h(y)dy . \tag{2}$$

My question:

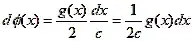

What is the physically intuitive meaning of the integral term?

For example, why does $\phi_t$ show up in the integral whereas $\phi$ shows up in the forward and backward waves? Why does the integral have those specific limits of integration (and region of integration) for $h$ whereas $g$ uses only the end points, $x+ct,x-ct$? Are there examples with specific functions for $\phi$ that would help to understand this?

References:

http://mathworld.wolfram.com/dAlembertsSolution.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%27Alembert%27s_formula

http://www.jirka.org/diffyqs/htmlver/diffyqsse32.html

http://people.uncw.edu/hermanr/pde1/dAlembert/dAlembert.htm

math.ualberta.ca 337week0405.pdf after equation 180.

stanford univ waveequation3.pdf page 4 Lemma 3 and page 5.

math.nist.gov evolution.pdf page 537

math.usask.ca lamoureax_michael.pdf page 19.

univ. of penn. m425-dalembert-2.pdf first three pages.

univ. of ill. at urbana 286-dalemb.pdf

"Generalized Functions, vol 1", I. M. Gelfand, G. E. Shilov, page 114

"Mathematics for the Physical Sciences", L. Schwartz, pages 253-257

"The Mathematical Theory of Wave Motion", G. R. Baldock, T. Bridgeman, pages 40-45

From these, for example, I know that for a string $\phi_t(0,y)$ represents the velocity at time zero, but why physically (and intuitively) does it end up in the integral. Or I know $(x+ct),(x-ct)$ define the edges of a cone with vertex at $(x,t)$ which form the boundary of the region of the argument of $h$ where $h$ can effect $\phi(t,x)$, but why does the integral have those specific limits of integration for $h$ whereas $g$ uses only the end points, $x+ct,x-ct$?