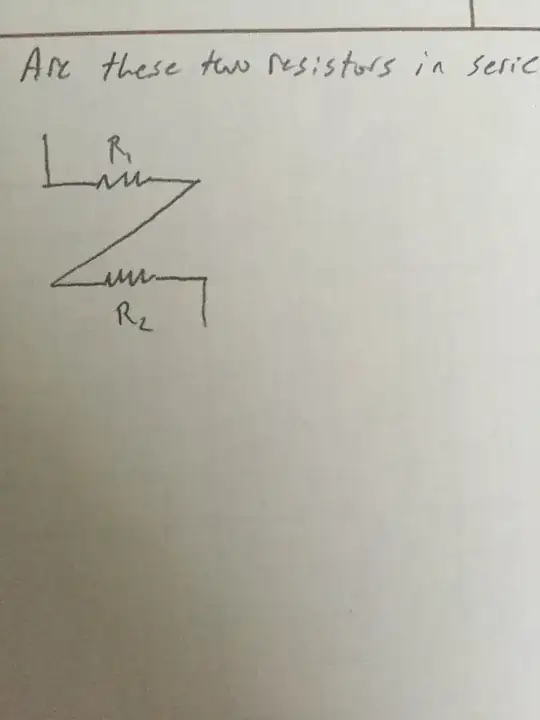

Resistors are in series if they are connected "end-to-end." In a series configuration, the current that flows through one resistor is the same as the current flowing through the other because that current has no where else to go. In this configuration, the voltage across the entire circuit is divided between the resistors.

Resistors are in parallel if there is a wire connecting one side of each resistor to eachother, and a wire connecting the other side of each resistor to eachother. Thus the resistors act like parallel lanes of traffic, each letting current through independently of what the other resistor is doing. In this configuration, the voltage across each resistor is identical to the voltage across the circuit, because the ends of each resistor are tied together with a wire. If, somehow, there was a difference in voltage, current would flow through the wire to rapidly equalize it (you wont see this until you get into really high frequency signal analysis... don't worry)

This is an example of a sort of problem where the waterflow metaphor for electrical circuits is very effective at visualizing what is going on in the circuit. In this metaphor, the pressure of the water corresponds to voltage, and the volume of water flowing through a hose corresponds to the current (the flow of electrons through the wire). More pressure/voltage means the water flows faster (more current). A resistor can be thought of as an impingement in these hoses, like putting your finger over the end of the garden hose. It lets current through, but slows it down. The more voltage you have the more water flows.

Using this metaphor, if we see that water which flows through one resistor/impingement must go through another resistor/impingement, then they are in series. If we can see a fork where the water can go through one resistor or the other, they are in parallel.

Think about what happens when you put your finger over the end of a hose. If you barely put it over the end, lots of water comes out, but at low pressure. If you almost fully cover the end of the hose, very little water comes out, but at much higher pressure. If we think about this as a circuit, we have two resistors. One is the impingement from your finger, which is a low resistance in the first scenario and a high resistance in the second. The other resistor is the faucet, where the water has to twist and turn through the valve. This resistance is constant between both examples.

In the first example, we see very little pressure-drop across your finger, but a lot of flow. This is because your resistance is low compared to the resistance of the faucet, so most of the pressure-drop across the whole system occurs in the faucet (ever think about that?). When you close down the end of the hose, now the resistance is high compared to that of the faucet, and most of the water pressure from your house pushes against the resistance caused by your finger, so you feel a lot more pressure. However, because you raised the resistance of the whole system, the total flow is lower.

We can see that this is a series configuration. 100% of the water going from the faucet has to go past your finger at the end of the tube. Thus the resistance of the faucet and the resistance of your finger are in series.

Now let's hook up two hoses from two different faucets. You hold one, with your finger over it, and your friend holds the other. The resistances of your finger and that of your friend are in parallel (and technically, each one is in series with one faucet's worth of resistance too). If you try to stop down your hose with your finger, you will get a strong spray of water, but your friend will be unaffected. They have the same pressure/voltage you do, so it really doesn't matter how much water flow/current goes through your pipe.

Let's mix it up a bit, and put a Y fixture in, with two hoses. You hold one, with your finger over it, and your friend holds the other. The resistances of your finger and that of your friend are in parallel. The current can either flow from the faucet through your hose into the air, or it can flow from the faucet through your friend's hose into the air. They start from a common point, and end at a common point, so they are in parallel. This parallel group of resistors is also in series with the faucet (yes, you can describe circuits in this way). In this case, when you push your finger down hard on the end of your tube, you don't get the high pressure spray. Like before, your finger changed the resistance across your tube, but because both hoses come from the same source, at one pressure, and both end at the same destination, at one pressure, they have to have the same pressure/voltage across them. If your friend's finger is looser over the hose than yours is, you'll find the water adjusts to go through your friend's tube more! As you study electricity more, you'll find the same effect occurs if you have parallel resistors in series with a third resistor!