Why don't we call the fermions in the standard model force carriers?

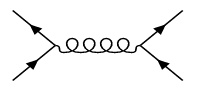

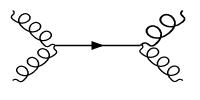

Because the Standard Model is what it is. By the way, I think it's far less complete than people make it out to be, and that it comes with some unfortunate baggage. Consider for example an electron and a positron interacting. People say they interact via virtual-photon force carriers:

CCASA image by Manticorp/Rubber Duck, see Wikipedia

CCASA image by Manticorp/Rubber Duck, see Wikipedia

But see anna's answer here and note this: "virtual particles exist only in the mathematics of the model". The electron and the positron are not throwing photons at one another. The only particles present are the electron and the positron. So in truth these fermions are the "force carriers".

Maybe this is a chicken-and-egg problem, but couldn't we call all the bosons fundamental and treat the fermions as force carriers between them?

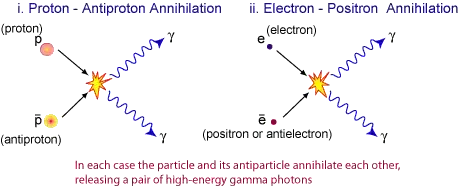

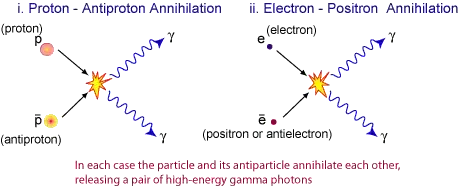

You could say that photons are "more fundamental" than other particles, in that you can reduce fermions down to photons:

Image credit CSIRO, see The Big Bang & the Standard Model of the Universe

But photons interact with photons, and with electrons, and electrons interact with electrons etc, and neutrinos are more like photons than electrons. So it wouldn't be right to treat the fermions as force carriers between bosons.

EDIT: After all we never see the asymptotic states of tree level Feynman diagrams. We can only measure an electron if it interacts with our measuring apparatus again, producing a photon...

Don't forget electron and positron tracks in a magnetic field. Or that Feynman diagrams shouldn't be taken literally.

EDIT2: Still not satisfied with the answers. Fermions always appear up to quadratic order in the Lagrangian of the Standard Model. We could easily integrate them out in the Path integral and describe our world solely with interacting bosons.

Sounds like a plan. After all, what does pair production really do? Remember that in atomic orbitals, electrons "exist as standing waves". What do you think they exist as outside of an orbital? What with electron spin and magnetic moment and the Einstein de Haas effect and the Poynting vector, and the wave nature of matter and the wave in the box, you don't have to be the Brain of Britain to work out that the electron is just a 511keV photon in a closed chiral spinor path. And that electrons and positrons interact the way that they do because of the way that they are: