The full equation

$$ Xf = X_o + V_o t + \frac{at^2}{2} $$

is integrated from the velocity function (which was integrated from constant acceleration function), right?

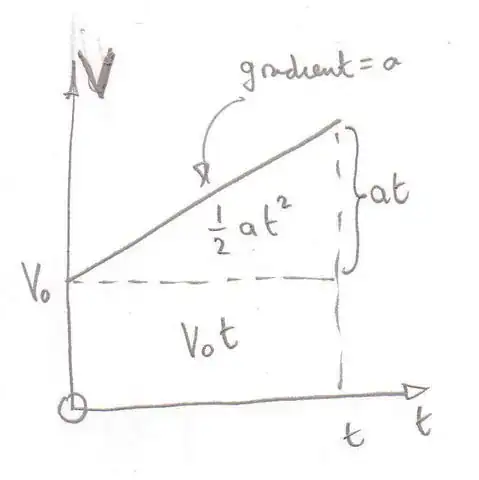

The problem is, I can't seem to put my mind around why the acceleration part needs to be halved.

Doesn't $at$ already measure the change in velocity over time? Why not just add that to the velocity then use the new V to measure Xf?