I (and we all) know that acceleration due to gravity $g\propto\frac{1}{r^2}$.Now my question is can I use this for depth.If not,why?If we can use it for depth or not struck me when I was trying to prove that acceleration due to gravity at center of earth is zero (hence weightlessness).If I use the above formula that the value of $g$ tends to infinity and not zero(I put radius equal to 0).Please help me with the limitations of the above formula and how to prove that $g$ is zero at the center of the earth where radius is zero.

2 Answers

If you have a spherical body of radius $R$ with mass $M$, the gravitational field at any point at a radial distance $r$ is given by: $$\phi=\frac{GM(r)}{r^2}$$ where $M(r)$ is the mass enclosed inside a spherical shell of radius $r$. This is the only mass that matters in this case. (because of the Shell Theorem: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_theorem)

$M(r)$ is: $$\int_V\rho \ dV $$ where $\rho$ is the density and $V$ is the volume of the spherical region. (This integral is automatically zero for regions where there is no mass present, so this would evaluate to $M$ in any region which completely encloses the sphere.)

For the interior of a spherical mass distribution (with uniform density), $$M(r)=\frac{Mr^3}{R^3}$$ (This simply is $\rho V(r)$ in this case, because we've assumed the mass density to be constant.)

and hence the field expression in the interior of the body is: $$\phi=\frac{GMr}{R^3}$$ which is zero for $r=0$.

This is true for all mass distributions with spherical symmetry. (i.e those that only vary with $r$)

In a quite simpler way, you could arrive at this from symmetry. If there is some gravitation field at the center of a uniform mass distribution, which way would it move your test mass?

- 7,538

Limitations of $g \propto \frac{1}{r^2}$:

The relationship

$g(r) = G \frac{M}{r^2} \rightarrow g \propto \frac{1}{r^2}$

(where $g$ is the acceleration due to gravity, $G$ is the universal gravitational constant, and $r$ is the distance between the massive object and the accelerating object) is just fine in Newtonian physics—it doesn't need to be fixed. Its only limitations are in the context of general relativity, wherein gravity is much more complicated. (Well, that and the fact that it assumes the massive object is infinitely small, which is the crux of your question!)

Can we use depth as a coordinate?

Let's define depth $d$ as

$d = R-r$

where $R$ is the radius of the spherical object. (Hence $d=R$ at $r=0$ and $d$ is negative when $r>R$.) Equivalently, $r=R-d$. Now, let's plug this into the formula above:

$g(d) = G \frac{M}{\left(R-d\right)^2}$

Even here, we can see that if $d\rightarrow R$ (e.g. at the center where $r=0$), we're getting infinite gravity. This isn't right. This is because we used a formula that assumed that the massive point is infinitely small, and we're interested in the gravitation at the center of an extended object (i.e. an object that has volume). If all of the Earth's mass were concentrated at the center, and $R$ took on any finite value, that formula would be valid. Since it isn't, we'll need a new approach....

The Real Answer

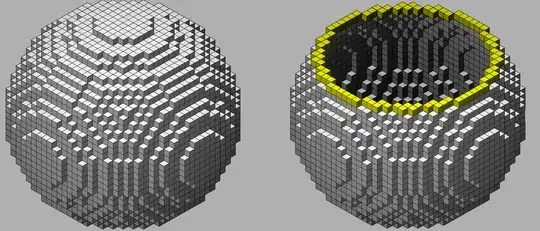

An extended object can be thought of as being made of an infinite number of smaller point objects, sort of like as in this diagram:

Each of those little masses $m_i$ is going to exert its own little force which will cause a little gravitational acceleration $g_i = G \frac{m_i}{r_i^2}$ (where $r_i$ is the distance from the little mass $m_i$ to the thing being accelerated).

One can show that if you have a spherical shell of uniform density, then the force of gravity inside that shell is zero, by summing up the forces from all of the little point masses in that shell. The force of gravity outside that shell is equal to the force of gravity if the mass of the shell were contained at a point in the center of the sphere. This is called the Shell Theorem, and is described in more detail here.

As a result, if you're in the middle of a ball with constant density $\rho$, you should think of the ball as a bunch of concentric spherical shells. All the shells above you are not contributing a net force on you. All the spherical shells below you are contributing as if all of their mass was contained at the center. Effectively, the force of gravity at radius $r$ from the center can be calculated via $g(r) = G \frac{M(r)}{r^2}$, where $M(r)$ is the mass of all the layers beneath you (i.e. a ball of mass $M(r) = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho$).

Thus, the net force of gravity a distance $r<R$ from the center of the ball is

$g(r) = G \frac{M(r)}{r^2} = G \frac{\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \rho}{r^2} = \frac{4}{3}\pi G \rho r$

If you don't know the density of the ball offhand, but you know its total mass $M$ and its radius $R$, then its density is

$\rho = \frac{\text{mass}}{\text{volume}} = \frac{M}{\frac{4}{3} \pi R^3} = \frac{3 M}{4 \pi R^3}$

We can plug this into our equation for the gravity at any radius $r<R$:

$g(r) = \frac{4}{3}\pi G \rho r = \frac{4}{3}\pi G \left(\frac{3 M}{4 \pi R^3}\right) r = G M \frac{r}{R^3}$

Note that the $\frac{r}{R^3}$ term looks almost like the $\frac{1}{r^2}$ term. That means the units work out.

Lastly, to calculate this in terms of depth $d = R-r$:

$g(d) = G M \frac{R-d}{R^3}$

Thus, at the center of the ball, when either $r\rightarrow 0$ or $d \rightarrow R$, we can see that the net gravitational acceleration is zero:

$g(d=R) = G M \frac{R-R}{R^3} = 0$

- 280