Since cables carry electricity moving at the speed of light, why aren't computer networks much faster?

Perhaps I can address your confusion with a rhetorical question:

Since air carries sound moving at the speed of sound, why can't I talk to you much faster?

The speed of sound is much slower than light, but at 340 m/s in air, it's still pretty damn fast. However, this isn't the speed of the channel, it is its latency. That is, if you are 340 meters away, you will hear me 1s after I make a sound. That says nothing about how fast I can communicate with you, which is limited by how effectively I can speak, and how well you can hear me.

If we are in a quiet room, I can probably speak very quickly and you can still hear me. If we are far apart or the environment is noisy, I will have to speak more slowly and clearly.

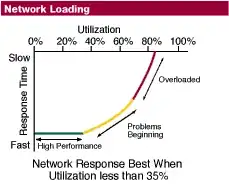

With electrical communications the situation is much the same. The speed limit is not due to the latency, but rather how fast one end can transmit with the other end still being able to reliably receive. This is limited by noise picked up from the environment and distortions introduced by the cable.

As it turns out, especially for long distances, it is easier (and more economical) to manufacture a fiber optic cable that does not permit outside interference and introduces very little distortion, and that is why fiber optic cables are preferred for long distance, high speed networking.

The reasons for optical fiber's superior properties are many, but a significant development is single-mode fiber. These are fibers which, through carefully controlled geometry and research clever enough to earn a Nobel prize, support electromagnetic propagation in just one mode. This significantly reduces modal dispersion, which has the undesirable effect of "smearing" or "spreading" pulses which encode information. This is a kind of distortion that if excessive, renders the received signal unintelligible, thus limiting the maximum rate at which information can be transmitted.

A further advantage is that fiber optic communications operate at an extremely high frequency, which reduces chromatic dispersion, a distortion due to different frequencies propagating at different speeds. Typical wavelengths used in fiber are in the neighborhood of 1550 nm, or a frequency of around 193000 GHz. By comparison, category 6a cable is specified only up to 0.5 GHz. Now, in order to transmit information we must modulate some aspect of the signal. A very simple modulation would be turning the transmitter on and off. However, these transitions mean the signal can not consist of just one frequency of light (Fourier components), so the different frequency components of the pulse will be subject to chromatic dispersion. As we increase the carrier frequency but hold the bitrate the same, the fractional bandwidth decreases. That is, the transitions from the modulation become slower relative to the carrier frequency. Thus, chromatic dispersion is decreased, since the signal becomes more like just one frequency of light.

Modern single-mode fiber is so good that the information rate is usually limited by our technology to manufacture the receivers and transmitters at the ends, not by the cable. As an example, wavelength-division multiplexing was developed (and is constantly improved even today) to allow multiple channels to coexist on the same fiber. Several times, networks have been upgraded by upgrading the transceivers at the ends, leaving the cable unchanged. Considering the cost of upgrading a transcontinental cable, the economic advantage should be obvious.