Everyone agrees that there are twelve Olympians, but the identities of the twelve seems to vary. What is the deal?

5 Answers

The shift has to do with Hestia originally being one of the twelve; then when Dionysus became a god, she gave up her throne for Dionysus. Interestingly enough, this unbalanced the council; there were then 7 men and 5 women. These were

- Zeus

- Hera

- Ares

- Athena

- Apollo

- Artemis

- (initially) Hestia (then later) Dionysus

- Poseidon

- Aphrodite

- Demeter

- Hephaestus

- Hermes

These specifically were the main twelve for several reasons:

- Seniority

A couple were direct children of Kronos, namely Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, and Demeter (and Hestia, but she gave up her seat for Dionysus; and not Hades, see below). This puts five on their seats fairly clearly.

- Purpose

The remaining gods were major in that they had governance over important things - Ares, god of war, Athena, goddess of war and wisdom, Hephaestus, god of blacksmithing, clever workmanship, and fire, Apollo, god of poetry, archery, sickness and healing, prophecy, and the sun (which he sometimes gave up to Helios, the Titan), Artemis, goddess of hunting, the moon (sometimes given up to Selene, the Titan), virginity/young women, children, and also archery, Dionysus, god of wine (wine was a lot more important back then because water was not safe to drink in most cases; therefore wine was more commonly consumed as the alcohol killed the germs/bacteria/gross stuff), Hermes, god of messengers, travelers, thievery, games of chance, cattle, and all that good stuff, and Aphrodite, goddess of love.

No one put minor gods and goddesses on the council because they just weren't important enough. Could you imagine have the god of bee-keeping and cheese-making on the council (Aristaeus)?

And then there was Hades. The reason he (and Persephone his wife) weren't on the council was because they were kind of scary, and he just didn't visit Olympus much. He had his own realm to handle (the Underworld).

There are many lists of the Twelve Olympians, and one can make an argument that any of the gods should or shouldn't be included. One of the most common lists is Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Artemis, Ares, Hermes, Poseidon, Demeter, Hephaestus, Aphrodite, Athena and Dionysus, and the Hestia gave up her seat in the Olympian throne room to Dionysus. This is the most popular list of the Twelve Olympians and is the one that is generally accepted by people who don't care too much. Although, really, why does it matter? There is no reason to group the Greek Gods by who had a throne on Mt. Olympus. I would argue Hades is much more important and powerful than Dionysus or Hephaestus. If we're grouping them by power level, Eros should really be on the list, considering many texts state that it is said that he is an entity feared by Zeus himself.

Tl;dr Usually the most common list has Hestia giving up her seat for Dionysus, but there is really no reason to group the Greek Gods this way. Arguments can be made for anyone's inclusion or exclusion on the list.

- 312

- 1

- 3

TL;DR: The Greeks had a cult of twelve gods, but not a canonical list of members!

The Greek texts, however, stress the number of the gods, seldom revealing their names. […] The essential factor is the number. At the same time the members tend to be major named gods, usually of Greek origin. A majority of them may be Olympians because this group included the most widely recognized Greek gods, but they are not the Olympians per se. They are the twelve chief gods of a given community or individual at a given time.

Charlotte R. Long (1987). The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome, page 141. Leiden: Brill.

The Greeks had a cult of twelve gods …

Furthermore, the Egyptians (they said) first used the names of twelve gods (which the Greeks afterwards borrowed from them) […]

When the Athenians were making sacrifices to the twelve gods, they sat at the altar as suppliants and put themselves under protection.

Herodotus (c. 430 BCE). The Histories 2.4 and 6.108. Translated by A. D. Godley (1920). Perseus Digital Library.

And amongst many that had the annual office of archon [of Athens], Peisistratus also had it, the son of Hippias, of the same name with his grandfather, who also, when he was archon, dedicated the altar of the twelve gods in the market place† and that other in the temple of Apollo Pythius.

Thucydides (c. 400 BCE). History of the Peloponnesian War 6.54. Translated by Thomas Hobbes (1843). Perseus Digital Library.

† This altar currently lies under the Athens–Piraeus Electric Railway and has not been fully excavated.

After this they must also appoint twelve allotments for the twelve gods, and name and consecrate the portion allotted to each god, giving it the name of “phyle.”

Plato (4th century BCE). Laws 5.745. Translated by R. G. Bury (1968). Perseus Digital Library.

Coming from the Pontus, [the Propontis] begins at a place called Hieron, at which they say that Jason on his return voyage from Colchis first sacrificed to the twelve gods.

Polybius (2nd century BCE). Histories 4.39. Translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (1962). Perseus Digital Library.

On Lectum is to be seen an altar of the twelve gods, said to have been founded by Agamemnon. […]

Now the width of the mouth of [the Elaïtic Gulf] is about eighty stadia, but, including the sinuosities of the gulf, Myrina, an Aeolian city with a harbor, is at a distance of sixty stadia; and then one comes to the Harbor of the Achaeans, where are the altars of the twelve gods

Strabo (1st century CE). Geography 13.1.48 and 13.3.5. Translated by H. L. Jones (1924). Perseus Digital Library.

Along with lavish display of every sort, Philip [of Macedon] included in the procession statues of the twelve gods wrought with great artistry and adorned with a dazzling show of wealth to strike awe in the beholder, and along with these was conducted a thirteenth statue, suitable for a god, that of Philip himself, so that the king exhibited himself enthroned among the twelve gods. […]

Thinking how best to mark the limits of his campaign at this point, [Alexander] first erected altars of the twelve gods each fifty cubits high

Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE). Library 16.92 and 17.95. Translated by C. H. Oldfather (1835). Perseus Digital Library.

Zeus parted [Poseidon and Athena] and appointed arbiters, not, as some have affirmed, Cecrops and Cranaus, nor yet Erysichthon, but the twelve gods. […] Impeached by Poseidon, Ares was tried in the Areopagus before the twelve gods, and was acquitted.†

Pseudo-Apollodorus (1st or 2nd century CE). Library 3.14. Translated by James George Frazer (1921). Perseus Digital Library.

† One could infer from this text that, since the “twelve gods” were appointed by Zeus to arbitrate a dispute between Poseidon and Athena, and later to try a case brought by Poseidon against Ares, the twelve did not include these four! This demonstrates, I think, the way in which the “twelve gods” existed independently of any particular membership list.

For a multitude of similar citations, see Long, pages 49–136.

… but not a canonical list of members!

Since the cult of the twelve gods is mentioned by so many of the important Greek writers, it is at first surprising that none of them list the twelve. Perhaps one author or another might have omitted the list because it was common knowledge, and did not need explaining, but all of them? For a list of names, we have to reach as far as a scholiast on Apollonius of Rhodes.

These are the Twelve Gods: Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Hermes, Hephaistos, Apollo, Demeter, Hera, Hestia, Artemis, Aphrodite and Athena.

Scholiast on Apollonius of Rhodes. Note on Argonautica 2.532. Translated by Charlotte R. Long (1987). The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome, page 55. Leiden: Brill.

This might seem definitive, except that a scholiast on Pindar says that Herodorus gave a different list:

For Herodorus the Grammarian [5th–4th century BCE] recounts concerning the six altars: Coming into Elis (Herakles) founded the sanctuary in Olympia of Olympian Zeus and made Olympia the district homonymous with the god. He set up here for him and for the other gods altars, six in number, a token of the Twelve Gods, and first that of Zeus Olympios whose colleague he made Poseidon; the second of Hera and Athena, the third of Hermes and Apollo; the fourth of the Charites and Dionysos; the fifth of Artemis and Alpheios; the sixth of Kronos and Rhea.

Scholiast on Pindar. Note on Olympia 5.10. Translated by Charlotte R. Long (1987). The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome, page 58. Leiden: Brill.

Pausanias mentions three of these double altars in Description of Greece 5.14, but they are in a list of other altars and he gives no indication that they belong together. Charlotte Long comments (page 156), “it appears that in [Pausanias’] time, ca. A.D. 150, the double altars were not grouped in a separate precinct nor even regarded as a set of Altars of the Twelve Gods. Consequently the cult, which was flourishing in the fifth century B.C., must have fallen into obscurity.”

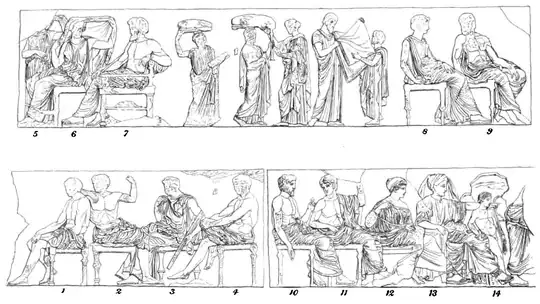

There are a number of extant artefacts possibly depicting the twelve gods: see Long, pages 1–48 for a catalogue. None of these gives us a list of names, and identification of the depicted figures is far from certain. The most famous of these is the east frieze of the Parthenon in Athens, which depicts twelve seated and two standing figures watching a procession. The blocks and fragments from the frieze are now in the British Museum in London and the Acropolis and National Museums in Athens, but can be assembled as shown below (figures 1–4 belong to the left of 5, and 10–14 to the right of 9).

Thomas Davidson (1882). The Parthenon Frieze, page ii. London: Kegan Paul, Trench.

Long identifies these figures as 1. Hermes 2. Dionysus 3. Demeter 4. Ares 5. Nike or Iris 6. Hera 7. Zeus 8. Athena 9. Hephaistus 10. Poseidon 11. Apollo 12. Artemis 13. Aphrodite 14. Eros. However, these identifications are not certain:

An enumeration of the attempts that have been made to identify the gods of the frieze, in order to find the principle of their arrangement, would fill a volume, and these attempts are still continued. Most frequently, it is true, some principle is arbitrarily adopted, and then the gods are named so as to conform to it; whenever the opposite method has been pursued, it has proved absolutely impossible to find any single or rational principle of arrangement.

Davidson, “to show how utterly problematical the whole matter is”, gives a table, on pages 46–47, of identifications made by earlier authors. For example, figure 2, identified as Dionysus by Long, has variously been identified as Polydeukes, Triptolemos, Herakles, Poseidon, Theseus, Eumolpos, Hephaistos, and Apollo.

So the Parthenon frieze doesn’t resolve our uncertainty, and even if it did, it would only show one assignment of names to the twelve gods at one place and time. Considered as a whole, the evidence suggests that the cult of the twelve gods was in some sense independent of the individual identities: the number came first, and the identities could be filled in as necessary from the locally most important divinities.

- 645

- 4

- 12

The Twelve great gods of the Greeks were known as the Olympians. Together they presided over every aspect of human life. The goddess Hestia (listed here in the second rank) was sometimes included amongst the Twelve.

So going with the list provided

- Aphrodite

- Apollo

- Ares

- Artemis

- Athena

- Demeter

- Dionysus

- Hephaestus

- Hermes

- Hestia (Part-time)

- Hera

- Posideon

- Zeus

They seem to vary because of the age of the sources, I believe earlier sources say that Hestia is one of the 12.

The 12 Olympians were:

Zeus

Hera

Poseidon

Demeter

Hephaestus

Athena

Aphrodite

Ares

Apollo

Artemis

Hermes

Hestia / (later Dionysus): Hestia gave up her throne to Dionysus for a place next to the fireplace. https://greekmythology.wikia.org/wiki/Thrones_of_the_Gods

It is considered at many places that Hades is also one of the Olympians as he is one of the main off springs of Kronos and Rhea who helped Zeus defeat Kronos and throw the other Titans in Tartarus, however, he does not have a seat at the Mount Olympus as he needs to stay in the underworld in order to rule it.

- 194

- 9