The common wisdom is very wrong.

People used to retire at age 65 with a pension from a large company and some savings. 50 years ago, if you lived to 65, your expected lifespan was less than 5 years. Today if you live to 65 in the U.S., your expected lifespan is to the mid-80's. And, of course, some people will live longer. So you need to plan to age 95 to be safe.

Today, few people have a pension - they have their own savings, likely in a 401|(k). Let's suppose that is the case. |And let's suppose you have saved $600,000.

The wrong way to think about this is 'let me move it all to bonds and live off the interest'. Why? (1) you would only get, at best, 3% interest. That's only $18,000 per year, and (2) taxes will be very high on bond income.

But its worse. If it is currently in stock you bought long ago, you would need to sell that first to buy bonds. Suppose you have a 25% tax rate; if it is a 401(k) maybe 33%. SO, right away you have reduced your $600,000 to $400,000 to $450,000. At 3%, that pays $12,000 to $13,000 per year.

Really, over the long-run - and 30 years is the long run - the stock market is a better bet. People worry too much (like in the post above) about a recurrence of 2008. But, that is a very rare occurrence. In reality, the market goes up on average about 8-10% annually. And, dividends are about 2% as well. So, $600,000 will pay you about $12,000 in dividends or so per year.

Plus, on average, the stock goes up $48,000 to $60,000 per year on top of that. So you can spend some of those profits as well (which, like dividends, will be taxed at 15%, or 20% at most - unless in a 401(k). Even if markets are anemic, or you are conservative, you can spend likely $30,000 plus the $12,000 of dividends - $42,000 - and at that rate the account would keep going up in value as well.

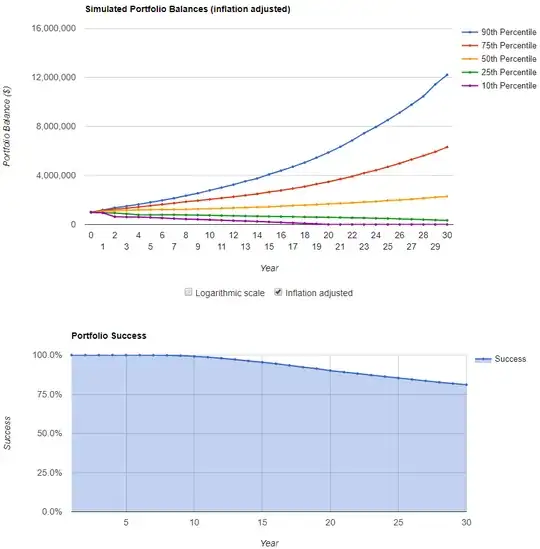

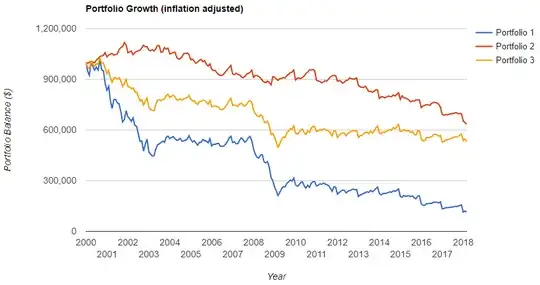

People worry way, way too much about a market meltdown. If you have 30 years to plan for, you will live through one or two. But unless you have so little money that a 25% drop in a single year that recovers over the next 4 years (sort of what happened), stocks are a much better investment.

Here is a great old rule. Whatever percent you ear, divide 72 by that number and that is how long it takes to double your money. Even if you get 7%, in 10 years your account doubles. If that happens, and a 30% market drop happens, you are still way ahead.

People focus way too much on the short-run and buy things like bonds. In many cases the only certainty they get, if they knew how to calculate it, is a certainty of going bankrupt before dying.