Counterfeit bills are a big problem for governments, so they periodically update their bills to add several security features aimed at preventing counterfeit bills.

But I imagine that for this to work, the old bills need to be removed from circulation, for example by setting an expiry date after which they can't be converted to newer bills and lose validity.

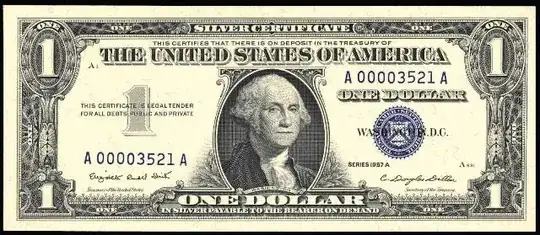

How do countries whose bills don't have an expiry date handle counterfeit? What prevents an expert counterfeit from printing money from the 1950's (which the government themselves believe to be insecure now) and making a profit? I believe that this is the case of the U.S., since the U.S. dollar bills do not have an expiry date.

Edit

Just to clarify, I am not talking about the viability of counterfeit in general. Since governments have deemed necessary updating bills with new security features, you should work with the assumption that counterfeit without those new security features is (or will become in about 10 years) feasible and profitable. So any explanation that applies to counterfeit in general (like matching serial bills, say) is automatically invalid.