Inflation linked (IL) bonds are available in several countries. They are also nothing new. The earliest recorded inflation-indexed bonds were issued by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1780 during the Revolutionary War.

Also, since you mentioned auctions in a comment, these are the standard way government bonds (all kinds, not just inflation linkers) are issued in the primary market. Once these bonds are on the secondary market, you can trade them without problems.

Governments of at least the following countries issue IL Bonds:

U.S., UK, France, Germany, Canada, Greece, Australia, Italy, Japan, Sweden, Hong Kong, Spain, Israel and Iceland and some emerging markets like Brazil, Mexico, Russia, India and the like.

Apart from single government bonds, there are various funds that invest in inflation linked bonds. See for example

Since you mention Germany, I assume you are not based in the US. To buy I bonds you’ll need to be one of the following:

- A U.S. citizen, even if you live abroad

- A U.S. resident

- A civilian employee of the U.S. government, regardless of where you live

The problems with inflation linkers:

They are kind of complex as you can probably tell from the question you linked. Even computing interest payments of a fixed rate bond accurately with daycount conventions, or the yield can be complex. However, IL are a very different story.

- Inflation-Indexed securities can have a negative yield as a result of yields being below (expected) inflation.

- Most IL bonds adjust the principal value with the CPI (so in case of deflation, you actually have a declining principal). Some countries like the U.S., Australia, France and Germany offer deflation floors at maturity, which mean that if deflation drives the principal amount below par, you will still receive the full par amount at maturity.

- Similarly, coupons payments vary as they are based on the adjusted principal (in this case there is no floor)

- ILB prices will increase as real yields decline and decrease as real yields rise. If you hold them to maturity, that will not be a real problem.

- If you invest in funds or ETFs, you have an additional problem, namely that they have no maturity date. Since TIPS are highly sensitive to interest rate movements, the value of a TIPS mutual fund or ETF can fluctuate widely in a very short period, and you are not guaranteed to get your principal back.

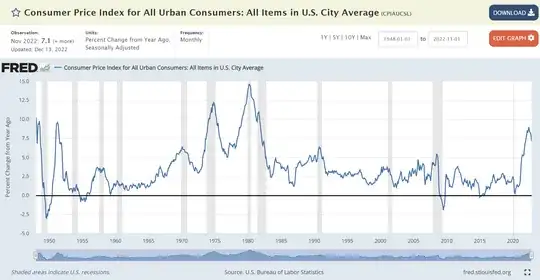

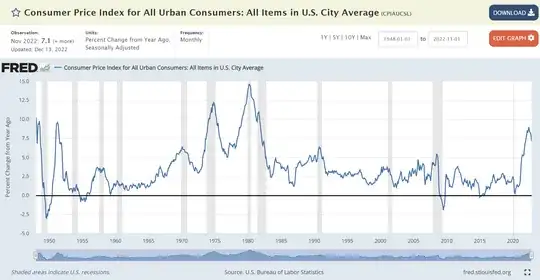

Overall, they do offer a good inflation hedge though and can be a valuable addition to a diversified portfolio. Why not everyone buys them? Many people do not even know they exist, some who do find the mechanics difficult, others tried, and lost confidence when there was very low inflation or deflation. After all, many countries like the U.S. have not really experienced substantial inflation since 1981.