First the mandatory disclaimer: It is very hard to actually know whether you're in a bubble. I know you said to assume you do, so I won't argue with the premise, but it's worth noting that this is actually a very unrealistic hypothetical.

The problem as stated is not tractable. Knowing that you're in a bubble is like knowing you're going to die. It's useless "knowledge" because you are missing two critical pieces of the puzzle:

- When (the bubble will pop)

- How (high will the top be and how far it will drop)

Without this, there's not much action you can take. I had a lot of bitcoin when it was less than $10. When it hit $1k I thought, surely this is a bubble and cashed out on 1,000% upside. I have missed out on 5,000% of upside. Recently Bitcoin did "crash" - from 60k to 30k, a giant 50% drop. It would still have been 3,000% upside. Hindsight is of course 20/20, but the point is that being in a bubble does not imply that:

- The bubble will pop soon

- The bubble will not go much higher yet

- When the bubble pops, it will go lower than now

By definition a bubble is an overvaluation, which seems to imply that when it pops, people will no longer overvalue, hence their final price must be lower and the third point must be true. Unfortunately, that is not so. Valuation is subjective and people are under no obligation to return to rationality -- arguably the markets have not had rational valuations for most of their existence. Moreover, as the saying goes, the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.

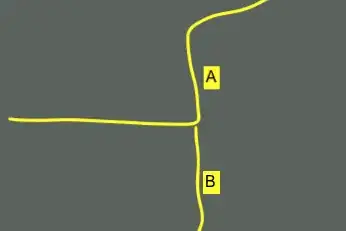

The constructive thing to do is to reframe the thesis as a bearish outlook. Hopefully, the same sort of evidence used to detect the bubble, can also support the bear thesis. Not to belabor the point, but note that saying we're in a bubble is not really bearish - it is also bullish since the bubble could keep going, so there's really not much directional information in it. Anyways, if your outlook is bearish, then you should sell assets. You can short them, literally sell them, buy inverse funds, buy puts, sell calls, and use any number of similar strategies. You could also just hold cash in anticipation of the bottom, or buy supposedly uncorrelated assets like precious metals. You could look at things like reverse mortgaging your house. Each of these strategies has variables that go into pricing, and depending on your knowledge of when the assets will come down, which ones and how much, and the respective certainties you have, you can figure out the best strategy and the best price. The details of this would be out of scope for this question.

If you are not able to support a bearish outlook, then it gets tricky. You could frame it as a volatility play - you don't know where exactly it will move, but you do expect it to move a lot. Then you can buy volatility indices or trade various option spreads like short butterfly.

In every case, you will likely need to do a bit more than merely buying and holding a security. You'd have to set up some limits, stop losses, trailing stop losses etc. to account for the uncertainty you are expecting in the price.

The above is what you can do on the rent-seeking front, without doing much work. Serious bubbles often bring economic depression when they pop, jobs become scarce, purchasing power goes down, things become expensive. So you might try to prioritize gaining skills, work experience and increasing your employability so that you can bounce back post-crash. However, the trouble is that crashes can change the job market a lot, so it's hard to say which jobs will be lucrative after the crash. But nevertheless, the general idea is simple: Prepay for things you need that are currently cheap, defer expenses that are inflated. Hope you can last long enough.