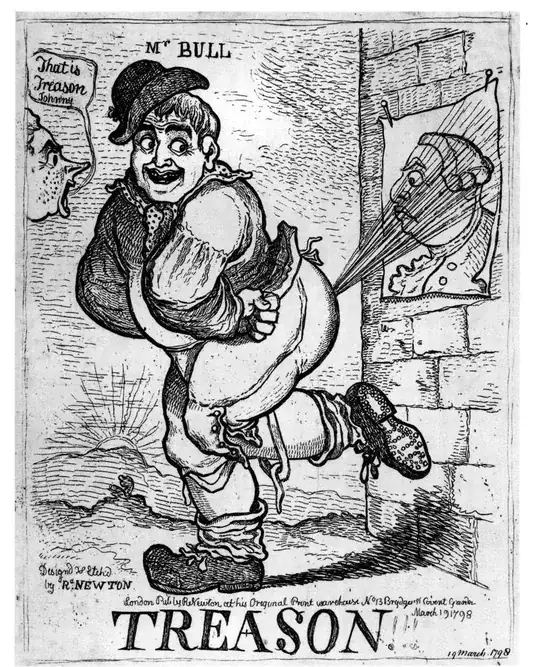

A famous political cartoon from 1798 by Richard Newton claims that farting on a picture of the British monarch would be prosecutable as "TREASON!!!" (caps and multiple exclamation marks in original).

Would this act actually qualify as Treason under English law in 1798?

According to the Treason Act 1351, treason consists of:

...when a man doth compass or imagine the death of our lord the King, or of our lady his Queen or of their eldest son and heir; or if a man do violate the King's companion,....or if a man do levy war against our lord the King in his realm, or be adherent to the King's enemies in his realm, giving to them aid and comfort in the realm, or elsewhere....

Farting on someone's picture is not the same thing as compassing or imagining their death, violating their heirs or companion, or levying war against them.

The Treason act 1702 covers attempts to interfere with the royal line of succession, not disrespecting a picture.

So, is there any truth to this cartoon? To be clear, I'm not asking whether it was socially acceptable in England of the 1790's to publicly pass gas on someone's picture (nor whether it is acceptable to do so today), but whether it fit the legal definition of Treason under any statutory or common law offense that would have been in effect in 1798.

More specifically, either of the following scenarios seems plausible:

- This was literally treason in 1798, and the cartoon's purpose is to point out the absurdity of treating toilet humor shenanigans as legally equivalent to murdering the king or waging grim war against him.

- This was not actually treason, but the point of the cartoon was a warning against contemporary trends in expanding the scope of criminal offenses to cover unusual or non-obvious scenarios. In other words, this was an exaggeration to emphasize that criminal law was getting so ridiculously broad that farting on a picture might soon be prosecutable as a major offense if the cartoon's readers didn't start advocating for more narrow and sensible laws.