The Prisoner's Dilemma is a well-known game theory problem that translates well into our real life experience. The idea is that two people who will optimize their individual and collective outcomes by cooperating can, under specific circumstances, decide not to cooperate.

Can the two prisoners solve their dilemma by mutually binding each other to silence with an enforceable civil contract of the nature of a Non-Disclosure Agreement?

Prisoner's Dilemma DescriptionTwo members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge, but they have enough to convict both on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is:

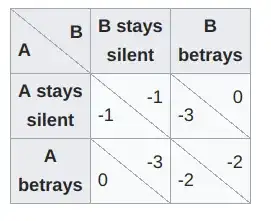

If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves two years in prison

If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa)

If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve one year in prison (on the lesser charge).

Edit

I don't think the following analysis applies:

It would not "solve" the problem, because the contract would not be enforceable. See this question on enforceability. In particular, Lachman v. Sperry-Sun Well Surveying Company, 457 F.2d 850

A bargain, performance of which would tend to harm third persons by deceiving them as to material facts, or by defrauding them, or without justification by other means is illegal.

But I do not think that analysis applies because there is no deception or fraud involved. Both parties have a fifth amendment right to not self-incriminate. The agreement would be for both parties to exercise their constitutionally protected rights by remaining silent. Prosecutors often solve this with immunity agreements for "unindicted co-conspirators" plus subpoenas to compel testimony and otherwise cooperation with investigation. However, I don't think that tactic can displace an individual's constitutionally protected right to "remain silent."