Can the company get away with defaulting on its debt without being

forced into involuntary bankruptcy?

A company isn't "getting away with defaulting on its debts" merely because it is not being forced into an involuntary bankruptcy.

The answer from Trish deals with when the threshold is met correctly (apart from the dollar amount referenced).

To recap that (as of 2023, with the dollar amount adjusted for inflation every three years, the dollar amount quoted in the textbook in the question ignores the inflation adjustment):

The Bankruptcy Code’s requirements for commencing an involuntary

proceeding are straight forward. The eligibility requirements, set

forth in Section 303(b)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code, direct that the

requisite number of petitioning creditors holding non-contingent,

undisputed, unsecured claims must hold an aggregate debt across all

petitioning creditors totaling at least $16,750.

(Source)

But a little bit of larger context is desirable for the purpose of understanding what is at stake.

Are involuntary bankruptcies a common means of debt collection?

No. Involuntary bankruptcies are an extremely uncommon means of debt collection.

Aside from the traditional path of pursuing a judgment against the

putative debtor in state court, one or more creditors—if certain

criteria are met—can force a delinquent debtor into a bankruptcy

proceeding through the filing of an involuntary bankruptcy petition.

Commencing an involuntary bankruptcy is a powerful remedy to secure

payment. However, involuntary bankruptcy cases account for less than

one percent of bankruptcy proceedings in the United States each year.

An involuntary bankruptcy “exists as an avenue of relief for the

benefit of the overall creditor body . . .[I]t was not intended to

redress the special grievances, no matter how legitimate, of

particular creditors . . . .” Wilk Auslander LLP v. Murray (In re

Murray), 900 F.3d 53, 59–60 (2d. Cir. 2018) (citation omitted). For

example, an involuntary bankruptcy is an appropriate tool to prevent

funds and assets from being dissipated to the detriment of creditors

or to ensure certain creditors are not receiving preferential

treatment or payments. Commencement of an involuntary proceeding is

also an effective way to provide a supervised forum to review the

debtor’s prepetition transactions and implement an orderly

liquidation. On the other hand, the case law and Bankruptcy Code are

clear that an involuntary bankruptcy filed for the purpose of settling

a two-party dispute will be dismissed. While a creditor may be in

technical compliance with the Bankruptcy Code, the risk of dismissal

remains where the bankruptcy court determines the petition was filed

in bad faith—for example to harass or exercise leverage over the

putative debtor.

(Source)

The norm is to file a debt collection lawsuit outside bankruptcy

The usual remedy when a company defaults on its debts is for an individual creditor to file a lawsuit to collect that debt (usually in state court), for the creditor to then win a money judgment in that lawsuit, and for the creditor to then use that money judgment to involuntarily seize assets of the company and debts that are owed to the company.

Creditors in debt collection lawsuits win outright the vast majority of the time (ca. 90%-98% of cases that are resolved on the merits or by a default judgment), and when the case isn't resolved on the merits by a judge or jury, the case is usually settled for a significant partial payment that couldn't have been recovered that fast through the formal legal process (e.g. with an owner or friend chipping it to make the case go away), or with a payment plan that pays off a good share of the debt over time. Simple contractual debt collection lawsuits are also typically resolved by the courts more quickly than other kinds of cases, such as car accident personal injury cases, or construction defect lawsuits.

In approximate round numbers, there are about 11 million simple contractual debt collection lawsuits filed in the United States every year, and about 9 million foreclosures, evictions, and tax lien enforcement actions filed every year in the U.S., of which, something on the order of a million of those cases are filed against businesses.<1>

Outside of bankruptcy, the assets of the debtor are distributed on a first come, first serve basis to whomever can manage to get money judgments and seize the company's assets first.

Filing a simple lawsuit to collect a contractually owed debt and enforcing that debt can be quite cheap in terms of legal fees. On a one off basis, it would often cost less than $10,000 of legal fees all in, and that amount can often be added to the debt owed. Collection agencies, using economies of scale, will often be willing to collect debts in the $1,000+ range for 33%-50% of the amount recovered depending upon the anticipated difficulty of the case.

The legal process of enforcing a money judgment against a company is more straightforward in many respects than enforcing a money judgment against an individual, because companies typically can't exempt any of their assets from creditors claims, while creditors of individuals are limited by exemptions from creditors for personal residences, modest personal household goods, IRA and retirement accounts, certain cash value insurance policies, and a large percentage of current wages paid to an individual.

<1> These estimates are based upon the number of state and federal cases of these types filed in Colorado each year, a state which is almost always close to the average nationally (based upon the annual reports of the relevant courts in the year 2015, scaled up by population, with the business case to individual case ratio estimated from the relative shares of bankruptcy filings). These are only rough estimates with perhaps a one significant digit precision, but they provide an order of magnitude sense of the number of collection lawsuits filed.

Viable businesses, but for debt service, often voluntarily file for bankruptcy

Frequently, companies will voluntarily file for bankruptcy to disrupt that process and allow the process of paying its debts to be conducted in a manner that permits the company to stay in business, resulting in greater payments to the creditors (collectively) than they would have seen had the company simply liquidated its business and ceased to operate.

Voluntarily bankruptcy filings are especially common for publicly held companies that can't pay their debts as they come due.

This is because all of their corporate bonds typically contain a covenant that causes the bonds to be in default when any money judgment against the company goes unpaid or more than 30-60 days without being bonded around, and a corporate bond trustee who represents all of the bondholders promptly files a lawsuit to collect all of the company's corporate bonds if this happens (which is a very simple lawsuit with few facts that are reasonably subject to dispute in most cases, since non-payment that can be proven by bank records is usually the only issue). So, if a publicly held company isn't paying its debts as they come due, it will have all of its assets seized (and will probably be placed in a third-party receivership in the meantime) in a matter of a few months. So, in order to retain control (and to keep getting paid significant salaries in the meantime), publicly held companies in these situations (who can easily afford good bankruptcy lawyers) typically file Chapter 11 bankruptcies if this happens.

A voluntary bankruptcy filing by a company only works, however, if the operating costs of the company, apart from debt service, are less than the revenues of the company when operated as a going concern.

If the business isn't viable as a going concern (especially in a closely held company), then the company often just gives up and walks away and lets creditor descend like vultures to snap up the remaining property of the company that can't be diverted to management compensation and insider debt payments (some of which can be rolled back into the pot for the creditors if a bankruptcy is commenced).

Involuntary bankruptcies are the rare exception

Involuntary bankruptcies are vanishingly rare.

For example, in 2023, there were 266 involuntary bankruptcy petitions filed in the entire U.S., out of a total of 18,926 business bankruptcies and 452,990 individual bankruptcies filed that year.

So, there is about 1 involuntary bankruptcy per 71 voluntary business bankruptcies (although an involuntary bankruptcy can actually be a business or individual bankruptcy), and there are about 21 debt collection lawsuits against businesses for every voluntary business bankruptcy. There is about one involuntary business bankruptcy per 1,500 debt collection lawsuits filed against businesses.

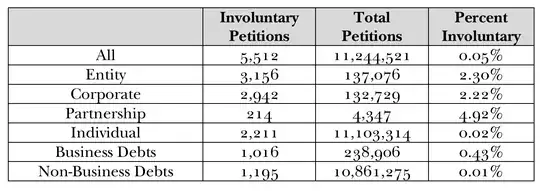

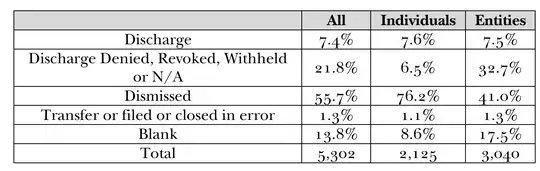

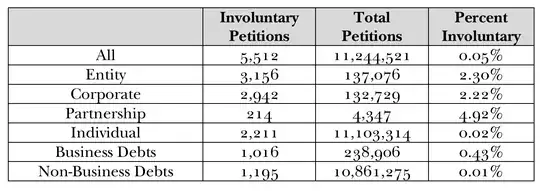

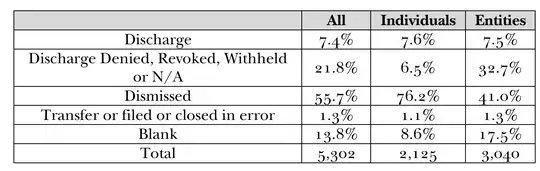

To some extent, the 266 involuntary bankruptcy filings per year is also an overstatement, because a significant share of involuntary bankruptcy filings are made as bad faith litigation tactics and are promptly dismissed. According to a 2022 law review article, "most involuntary bankruptcies are dismissed and that the dismissal rate for petitions filed against individual debtors exceeds 75 percent." (see the charts below with data for the decade from October 1, 2007 to September 30, 2017):

Involuntary bankruptcies that survive an initial dismissal are disproportionately in cases with mostly business debts. If you do the math, 79% of involuntary bankruptcies that survive an initial dismissal are entity bankruptcies. And, it is very likely that the remaining 21% of involuntary bankruptcies are disproportionately cases that involve business debts. The article that is the source of these statistics also notes that:

Involuntary petitions are not distributed evenly across the country.

The extremely high dismissal rate for individual cases is due in part

to the results in a single district: the Central District of

California. The Central District of California accounted for more than

a quarter (28 percent) of involuntary filings over the decade while

accounting for just seven percent of all bankruptcy filings. It played

an especially outsized role with respect to involuntary petitions

filed against individuals, accounting for nearly half (47 percent) of

these filings while accounting for just seven percent of all

individual filings. Individual involuntary petitions fared extremely

poorly in the Central District of California. Ninety-five percent of

these petitions were dismissed. Elsewhere the dismissal rate for

individual involuntary petitions was a still high 55 percent. For

entities, the Central District of California is less of an outlier, as

it had a dismissal rate of 43 percent and the rest of the country had

a dismissal rate of 40 percent. We are not sure why the Central

District of California has such a high number of involuntary petitions

or dismissals, but this bankruptcy district is unusual in other

respects. In particular, debtors in the Central District of California

file pro se voluntary petitions at a rate that is much higher than

the national average. It is reasonable to infer that some of the same

factors that induce debtors in the Central District to file pro se

voluntary petitions at an above average rate also induce creditors to

file pro se involuntary petitions there at a similarly high rate. . .

. [C]reditors filing involuntary petitions naming a natural person

debtor in the Central District almost invariably file pro se, and .

. . pro se involuntary filings are very likely to be dismissed.

Nationwide, about 41% of involuntary bankruptcy petitions are filed by pro se parties who basically just don't know what they are doing. And, even when those cases are not dismissed immediately, they are frequently dismissed for lack of prosecution or voluntarily withdrawn by the petitioner.

Thus, in a typical year in Colorado, there would be just 3 involuntary bankruptcies filed in the entire year in the entire state (and there would be a good chance that one or two of the three filed would be promptly dismissed).

A discharge is granted and an involuntary bankruptcy case in concluded following the completion of the entire bankruptcy process in less than 20 involuntary bankruptcy cases per year in the entire United States.

Why are involuntary bankruptcies filed?

Legitimate reasons to file an involuntary bankruptcy

The predominant reason that an involuntary bankruptcy is filed is to replace a first come, first served rule for distributing the company's assets to its creditors with a share and share alike rule, where all creditors with equal priority under the bankruptcy code get the share percentage of their debt paid.

Usually, a creditor legally savvy enough to file an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding would prefer to just get a money judgment and to get more than their fair share on a first come, first served basis of the company's assets.

But, on rare occasions, a number of smaller creditors who are legally savvy and capable for effective collective action for some reason (e.g. a group of unionized employees who are owed back wages) band together so that they can get something before a big creditor who is earlier in time but lower in priority than they are (e.g. a corporate bond trustee) gets everything or almost everything.

Another common fact pattern for an involuntary bankruptcy is one in which the principal assets of the company are at great risk of being sold at fire sale prices in an imminent foreclosure sale, and the involuntary bankruptcy is filed to increase the size of the pie available to creditors by securing a more commercially reasonable sale price for the assets being liquidated in foreclosure. In this situation, the company may not be fighting the foreclosure or soliciting higher bidders for the foreclosure sale, because it is deeply insolvent anyway, and the company doesn't care who ends up getting its assets since it will lose all of them anyway. Avoiding the bankruptcy and its possible impact on the credit of the managers of the company may be their higher priority.

A third fact pattern for an involuntary bankruptcy filing would be where there have been unjustified distributions to owners or low priority creditors or manager that the petition filer seeks to claw back as a "preference" into the pot of funds payable to creditors. Claw backs are also possible outside of bankruptcy in fraudulent transfer lawsuits accompanying a debt collection lawsuit, but this can be slower, and there is a real risk that the assets that were improperly diverted from the company will be dissipated by the time that relief can be secured in a state court lawsuit.

What does it cost to file an involuntary bankruptcy?

Filing an involuntary bankruptcy petition and following it through to the end would often cost $50,000-$150,000 in legal fees, which usually functionally ends up reducing the ultimate distribution to the creditors who bring the lawsuit (but not dollar to dollar, since some of the cost can be shifted to creditors who didn't hire the lawyers to file it), spread over the creditors who together hire the lawyer to make the involuntary bankruptcy filing.

But involuntary bankruptcy petitions filed without a lawyer are almost always dismissed immediately, dismissed for lack of prosecution, or voluntarily withdrawn by the people filing the petition.

Involuntary bankruptcy petitions as an improper litigation tactic

Sometimes involuntary bankruptcies are also filed for improper purposes as a litigation tactic, for example, to prevent a closing on the sale of a key intellectual property asset from going forward when a competitor who is also a creditor wants to buy it, or to disrupt a pending trial (e.g. in a products liability lawsuit) from going forward to delay that litigation, or to escape an unfavorable judge in a non-bankruptcy case. About 56% of involuntary bankruptcies are promptly dismissed, and only about 8% of involuntary bankruptcies are completely concluded without being dismissed for lack of prosecution or voluntarily withdrawn.

Sometimes a dismissal of an involuntary bankruptcy is a huge loss to the creditors filing it. But sometimes it is still a win for the creditors filing it even if it is dismissed, as it was really just a delaying tactic for the creditors to secure a non-bankruptcy case related advantage, and the creditors filing it assumed that it was likely to be dismissed in the first place.

A historical footnote

For the first centuries of bankruptcy’s existence, only creditors

could initiate a proceeding. “Voluntary” bankruptcy—initiated by the

debtor rather than creditors—began in the nineteenth century, but well

into the early twentieth century, involuntary bankruptcy accounted for

about two-thirds of the money distributed to general creditors. Today,

involuntary bankruptcy is a mere vestige. Just 0.05 percent of

petitions are involuntary, and most of those are summarily dismissed

without any court order formally commencing a bankruptcy case. . . .

early twentieth century bankruptcy practice provided de facto

incentives for involuntary petitions by rewarding filing attorneys

with lucrative post-petition work. Such rewards helped overcome the

collective action problems that otherwise discourage creditors from

filing. . . .

Bankruptcy began in sixteenth century England as a remedy for

creditors. Creditors initiated a bankruptcy proceeding by filing a

complaint against their debtor. Debtors could not file for bankruptcy

voluntarily in England or the United States until the middle of the

nineteenth century, and American corporations could not file

voluntarily until 1910. Yet, despite the late emergence of voluntary

bankruptcy, it has come to utterly dominate modern American bankruptcy

practice. Involuntary petitions filed by creditors now account for

less than 0.05 percent of all petitions. Even that meager number

overstates involuntary bankruptcy’s modern role because most

involuntary petitions are dismissed without a court even issuing an

order for relief to formally begin a bankruptcy case. . . .

Between 1920 and 1930 merchants and manufacturers accounted for nearly

three-quarters of the involuntary cases, and involuntary petitions

accounted for about 31 percent of merchant bankruptcies and just under

50 percent of manufacturer bankruptcies. By contrast, involuntary

petitions accounted for less than 0.5 percent of farmer or wage earner

bankruptcies, and farmers and wage earners together accounted for just

1.5 percent of involuntary cases. The real puzzle is why there were any involuntary petitions filed against farmers and wage earners, as

they were ineligible for bankruptcy relief. Perhaps these petitions

were filed by mistake. . . .

A modern reader might assume that manufacturers and merchants were

corporations. However, the corporation was not the organizational form

of choice for firms in the early twentieth century. Between 1899 and

1930, less than half of all (not just bankrupt) manufacturers in the

United States were incorporated. Even when owners chose to incorporate

their firms, they still could have ended up with substantial personal

liability. . . . The Attorney General’s reports for 1934 through 1939

list the number of bankruptcies by occupation and by type of debtor.

The Attorney General reports that during these years 73 percent of

bankrupt merchants were individuals, and 40 percent of bankrupt

manufacturers were individuals. . . .

Congress granted firms the ability to reorganize in bankruptcy in

1933, extended this power to public firms in 1934, and enhanced this

power by passing the Chandler Act in 1938. The relevant statutes

allowed both voluntary and involuntary petitions to start a

reorganization, but the availability of reorganization should have

made bankruptcy more attractive to debtors. To the extent that this

caused debtors to file voluntarily, it should have made involuntary

filings less necessary. . . .

By the early 1930s scholars and the bar noticed the incidence and

distribution of involuntary filings. In response to complaints about

the administration of bankruptcy law, the Donovan Report in 1931 and

the Thacher Report in 1932 documented numerous failures. Both

described corruption (particularly the Donovan Report) and

inefficiencies in bankruptcy administration, and proposed reforms.131

Among the described inefficiencies were bankruptcy procedures that

affected involuntary cases. Critics charged that the appointment of

the petitioning creditors’ attorney as the attorney for the receiver

led to a practice of “voluntary involuntary” or “friendly involuntary”

proceedings. This sort of proceeding involved the debtor’s attorney

providing the creditor’s attorney with a list of creditors and having

her file an involuntary petition against the debtor on behalf of

creditors on the list she was engaged to represent. Some practitioners

reported that as many as 90 percent of the involuntary petitions were

in fact orchestrated by the debtor. If true, the heyday of involuntary

petitions was more apparent than real. . . .

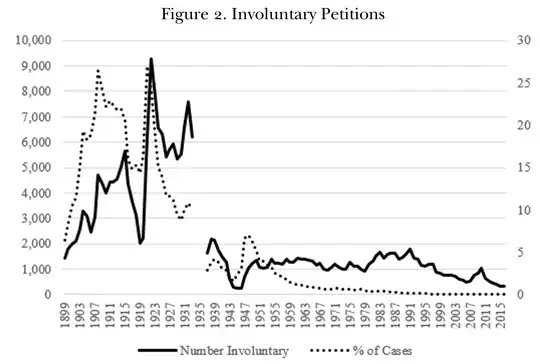

[W]hen in 1929 the Southern District of New York appointed a standing

referee and ended the practice of appointing the attorney for the

petitioning creditors as the attorney for the receiver, the percentage

of bankruptcy cases begun with an involuntary petition fell from 54

percent to 34 percent.

Other federal courts followed this practice of the Southern District of New York and this was a major factor in the decline of involuntary bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy law reforms adopted in 1978 made involuntary bankruptcy filings easier (by eliminating the need to have a jury trial before they commenced leaving the estate in the control of the debtor longer, and by making it easier to prove that an involuntary bankruptcy was necessary), but involuntary bankruptcies steadily continued to become less common anyway, possibly because the voluntary bankruptcy route became more attractive.

(From a 2022 law review article.)

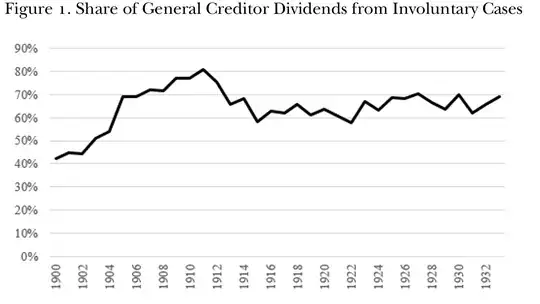

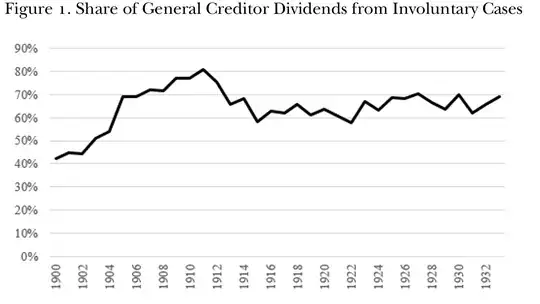

The chart above (from the same source) shows the percentage of all funds paid to general creditors in bankruptcies that came from involuntary bankruptcies (which the author argues are superior because they happened sooner before the companies were fully run into the ground).

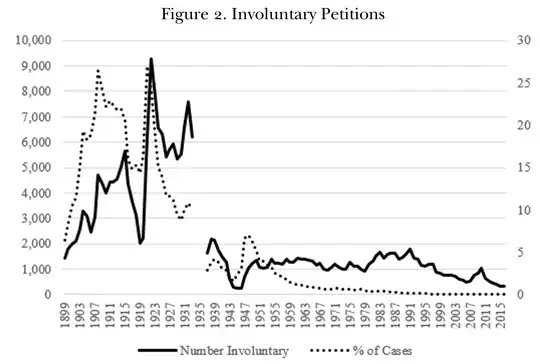

The chart above (from the same source) demonstrates that involuntary bankruptcy ceased to be common in the between 1934 and 1936.

A personal footnote

I will have practiced law for thirty years next month, and in all but a few of those years, I have dealt with a significant share of cases involving businesses not paying their debts as they came due. I've only seriously considered filing an involuntary bankruptcy two or three times in that time period. In the end, after careful analysis, it has never been the optimal choice for my clients, although in one of those cases is was a very close call.