Short Answer

This is a fairly close and complicated legal question, that is currently being litigated, that involves multiple, fairly technical and obscure issues of federal law.

It is much more likely that the tariffs are invalid entirely, because the President does not have the authority to impose them at all, than that they are substantively invalid for singling out particular industries or companies for special treatment according to a facially rational reason as this Executive Order does (despite the clear room for abuse and favoritism which is arguably present in this case).

But, the singling out of a particular industry in a way not set forth in existing tariff schedules arguably triggers notice and hearing requirements under the Administrative Procedures Act, which were not complied with in issuing this Executive Order (something that is a problem with many of Trump's Executive Orders upon which few courts have ruled yet in the first 100 days of Trump's second term when this answer is written).

Long Answer

Are the tariffs valid at all?

I understand these as broadly granting the president power to set

tariff rates, applied by category of thing being imported, during

(self-declared) emergencies.

Despite this claim of the President in multiple Executive Orders, this is probably not a correct understanding of the law. Several lawsuits challenging this authority on different grounds are currently being litigated in at least five lawsuits, including a lawsuit pending the U.S. Court of International Trade with several U.S. states joined as parties. Preliminary relief was denied by the court in at least one of those cases brought by a group of five companies.

There is good reason to believe that Trump does not have the legal authority to impose tariffs at all. Some of the reasons that he probably doesn't have that authority are:

(1) because the act he is relying upon for that authority doesn't expressly authorize imposing tariffs and this authority has never been relied upon by anyone other than Trump to impose tariffs (legal challenge to his first attempt to do so in his first term was mooted by a negotiated resolution of the trade dispute),

(2) because the authority he is relying upon to impose tariffs, if it does exist, has to be triggered by an "emergency" which there is virtually no factual basis to claim existed when he started imposing them,

(3) because it may violate the non-delegation doctrine of constitutional law for Congress to grant its taxing power to the President,

(4) because of the related "major questions" doctrine related to the non-delegation doctrine recently created by the U.S. Supreme Court,

(5) because it violates both World Trade Organization treaties,

(6) because it violates the treaties for the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement formerly known as NAFTA which Trump renegotiated in his first term, and

(7) because the actions taken violate the Administrative Procedure Act even if there was authority to impose the tariffs at all, since the notice and hearing requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act weren't followed.

Until recently, Trump would have received the benefit of the doubt regarding his interpretation of the referenced statutes under the Chevron doctrine established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984, which had required federal courts to defer to agency interpretations of federal law. But, on July 28, 2024, in the case of Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 603 U.S. 369, the U.S. Supreme Court's recently overruled the Chevron doctrine. So, Trump's interpretation of these laws are supposed to face de novo review by the courts, without any deference to the administration's views on the legal interpretation of the statutes upon which it relies, despite the fact that the agenda that enforces the statute takes the administration's position.

The notion that trade deficits on ordinary goods like car parts and clothing that are imported to the U.S. create a national security threat within the meaning of this law is dubious. President Trump is arguing in court that his declaration of an emergency is a non-justiciable political question that can't be second guessed by the Courts, but the notion that this particular determination is a non-justiciable political question is not a widely accepted legal theory.

According to the Congressional Research Service:

Summarizing the foregoing precedents, the CIT [Court of International Trade] has noted a "distinction between reviewing the substance of an exercise of discretion and reviewing an action for clear misconstruction of [a] statute, so that the authority delegated by Congress is exceeded."85 In the former scenario, the CIT explained, "this court lacks the power to review the President's lawful exercise of discretion."86 By contrast, "where statutory language limits the President, the court may review the executive's actions for 'clear misconstruction' of such limiting language."87

This Congressional Research Service report also explores other issues regarding the legal authority of the President to unilaterally impose tariffs in more depth than is possible in a Law.SE answer.

It wouldn't be impossible to write a rational judicial decision affirming Trump's ability to impose these tariffs, but there are multiple high legal hurdles that have to be overcome for this authority to be upheld.

Does creating arbitrary new tariff categories invalidate them?

Unilaterally establishing whole systems, where some dispreferred

people have to pay and other preferred people arbitrarily don't, is

very different and is exactly the thing one wouldn't assume an

executive to be authorized to do, because it's trivially abuseable.

Assume for sake of argument that Trump does have the authority to unilaterally impose tariffs, despite these concerns.

This is basically a 14th Amendment equal protection argument, and it probably meets the "rational basis" test need to overcome an equal protection challenge.

Yes, this Executive Order is being trivially abused to show favoritism. Basically the only U.S. automotive company that qualifies for this boon is Elon Musk's Tesla corporation, since no other U.S. automotive company has 85% or more domestic content for its vehicles. Not coincidentally, Elon Musk is literally a part of the Trump Administration to the point where pundits called him a "co-President" of the United States.

But, setting a threshold for U.S. automotive company content in a tariff calculated to prevent unfair foreign trade advantages and trade barriers (if, as Trump claims, they exist), would be a rational basis for distinguishing who does and doesn't get the tax break (if he has the authority to set tariffs exists at all). Congress could certainly make that kind of distinction, and routinely does so.

Realistically, any court willing to bend over backward to uphold these tariffs in the face of multiple very strong arguments that he doesn't have the authority to impose them at all would almost surely not be troubled by this very trivial challenge to the validity of this aspect of his tariff policy.

On the other hand, the Administrative Procedure Act challenge to creating this new distinction may have more legal weight.

Section 604 of the Trade Act of 1974 (which is codified at 19 U.S.C. § 2483, relied upon in the Executive Order, authorizes the President to change the categories of goods to which tariffs apply, seemingly directly addressing the question.

But, it isn't as simple as that, because this change of Executive Branch action is subject to the Administrative Procedure Act which requires changes to existing regulations, like the regulation setting forth categories of goods subject to tariffs, to be made only after notice and hearing. It can't just be done by a unilateral Executive Order without following Administrative Procedure Act rules.

One of the core purposes of the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946 was to discourage the use of Executive Orders issued as decrees without notice and hearing and deliberation.

Beginning in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Democratic

Congress enacted several statutes that created new federal agencies as

part of the New Deal legislative plan, established to guide the United

States through the social and economic hardship caused by the Great

Depression. However, the Congress became concerned about the expanding

powers that these autonomous federal agencies now possessed, resulting

in the enactment of the APA to regulate, standardize and oversee these

federal agencies.

The APA was born in a contentious political environment. Professor

George Shepard claims that Roosevelt's opponents and supporters fought

over passage of the APA "in a pitched political battle for the life of

the New Deal" itself. Shepard notes, however, that a legislative

balance was struck with the APA, expressing "the nation's decision to

permit extensive government, but to avoid dictatorship and central

planning."

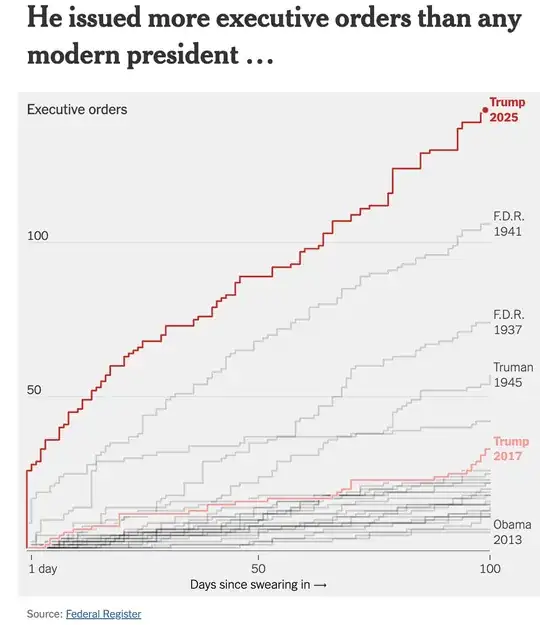

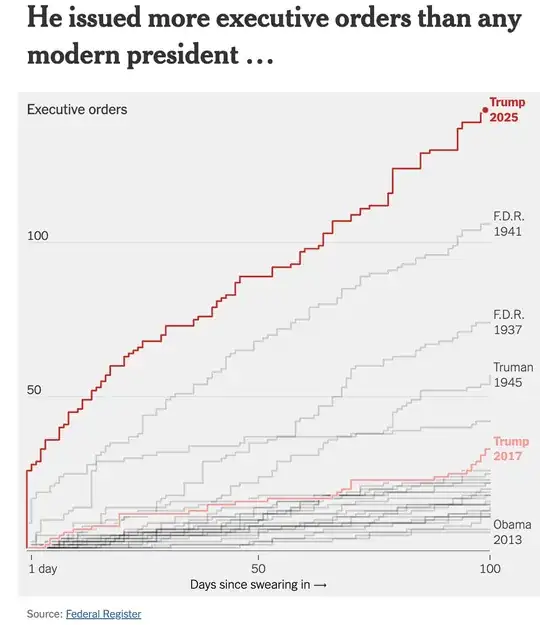

The existence of the Administrative Procedures Act is one of the main reasons that the current Trump Administration's heavy use of Executive Orders (as shown in the chart below) is unprecedented. The passage of the APA in 1946 greatly decreased the use of Executive Orders by subsequent Presidents.

From the New York Times.

The statutes relied upon in the Executive Order

3 U.S.C. § 301

3 U.S.C. § 301 relied upon in the Executive Order says (paragraph breaks not in the original and inserted for ease of reading in the Stack Exchange interface):

General authorization to delegate functions; publication of

delegations

The President of the United States is authorized to designate and

empower the head of any department or agency in the executive branch,

or any official thereof who is required to be appointed by and with

the advice and consent of the Senate, to perform without approval,

ratification, or other action by the President (1) any function which

is vested in the President by law, or (2) any function which such

officer is required or authorized by law to perform only with or

subject to the approval, ratification, or other action of the

President:

Provided, That nothing contained herein shall relieve the

President of his responsibility in office for the acts of any such

head or other official designated by him to perform such functions.

Such designation and authorization shall be in writing, shall be

published in the Federal Register, shall be subject to such terms,

conditions, and limitations as the President may deem advisable, and

shall be revocable at any time by the President in whole or in part.

So, this basically just says that the President can have a cabinet secretary deal with the details for him rather than doing it personally. This is uncontroversial and largely undisputed.

Section 604 of the Trade Act of 1974

Section 604 of the Trade Act of 1974 (which is codified at 19 U.S.C. § 2483, relied upon in the Executive Order says:

The President shall from time to time, as appropriate, embody in the

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States the substance of the

relevant provisions of this chapter, and of other Acts affecting

import treatment, and actions thereunder, including removal,

modification, continuance, or imposition of any rate of duty or other

import restriction.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (which is codified at 19 U.S.C. § 1862 (see also historical context for how this has been used here) is the substantive basis of Trump's claimed authority to impose tariffs without any other specific authorization from Congress, says (there are two subsections (d) due to a typographical error in the original act, and I have noted that with [sic] in the quotation above):

Safeguarding national security

(a)Prohibition on decrease or elimination of duties or other import

restrictions if such reduction or elimination would threaten to impair

national security

No action shall be taken pursuant to section 1821(a) of this title or

pursuant to section 1351 of this title to decrease or eliminate the

duty or other import restrictions on any article if the President

determines that such reduction or elimination would threaten to impair

the national security.

(b)Investigations by Secretary of Commerce to determine effects on

national security of imports of articles; consultation with Secretary

of Defense and other officials; hearings; assessment of defense

requirements; report to President; publication in Federal Register;

promulgation of regulations

(1)(A)Upon request of the head of any department or agency, upon

application of an interested party, or upon his own motion, the

Secretary of Commerce (hereafter in this section referred to as the

“Secretary”) shall immediately initiate an appropriate investigation

to determine the effects on the national security of imports of the

article which is the subject of such request, application, or motion.

(B)The Secretary shall immediately provide notice to the Secretary of

Defense of any investigation initiated under this section.

(2)(A)In the course of any investigation conducted under this

subsection, the Secretary shall—

(i)consult with the Secretary of Defense regarding the methodological

and policy questions raised in any investigation initiated under

paragraph (1),

(ii)seek information and advice from, and consult with, appropriate

officers of the United States, and

(iii)if it is appropriate and after reasonable notice, hold public

hearings or otherwise afford interested parties an opportunity to

present information and advice relevant to such investigation.

(B)Upon the request of the Secretary, the Secretary of Defense shall

provide the Secretary an assessment of the defense requirements of any

article that is the subject of an investigation conducted under this

section.

(3)(A)By no later than the date that is 270 days after the date on

which an investigation is initiated under paragraph (1) with respect

to any article, the Secretary shall submit to the President a report

on the findings of such investigation with respect to the effect of

the importation of such article in such quantities or under such

circumstances upon the national security and, based on such findings,

the recommendations of the Secretary for action or inaction under this

section. If the Secretary finds that such article is being imported

into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances

as to threaten to impair the national security, the Secretary shall so

advise the President in such report.

(B)Any portion of the report submitted by the Secretary under

subparagraph (A) which does not contain classified information or

proprietary information shall be published in the Federal Register.

(4)The Secretary shall prescribe such procedural regulations as may be

necessary to carry out the provisions of this subsection.

(c)Adjustment of imports; determination by President; report to

Congress; additional actions; publication in Federal Register

(1)(A)Within 90 days after receiving a report submitted under

subsection (b)(3)(A) in which the Secretary finds that an article is

being imported into the United States in such quantities or under such

circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security, the

President shall—

(i)determine whether the President concurs with the finding of the

Secretary, and

(ii)if the President concurs, determine the nature and duration of the

action that, in the judgment of the President, must be taken to adjust

the imports of the article and its derivatives so that such imports

will not threaten to impair the national security.

(B)If the President determines under subparagraph (A) to take action

to adjust imports of an article and its derivatives, the President

shall implement that action by no later than the date that is 15 days

after the day on which the President determines to take action under

subparagraph (A).

(2) By no later than the date that is 30 days after the date on which

the President makes any determinations under paragraph (1), the

President shall submit to the Congress a written statement of the

reasons why the President has decided to take action, or refused to

take action, under paragraph (1). Such statement shall be included in

the report published under subsection (e).

(3)(A)If—

(i)the action taken by the President under paragraph (1) is the

negotiation of an agreement which limits or restricts the importation

into, or the exportation to, the United States of the article that

threatens to impair national security, and

(ii)either—

(I)no such agreement is entered into before the date that is 180 days

after the date on which the President makes the determination under

paragraph (1)(A) to take such action, or

(II)such an agreement that has been entered into is not being carried

out or is ineffective in eliminating the threat to the national

security posed by imports of such article,

the President shall take such other actions as the President deems

necessary to adjust the imports of such article so that such imports

will not threaten to impair the national security. The President shall

publish in the Federal Register notice of any additional actions being

taken under this section by reason of this subparagraph . (B)If—

(i)clauses (i) and (ii) of subparagraph (A) apply, and

(ii)the President determines not to take any additional actions under

this subsection, the President shall publish in the Federal Register

such determination and the reasons on which such determination is

based.

(d) [sic] Domestic production for national defense; impact of foreign

competition on economic welfare of domestic industries For the

purposes of this section, the Secretary and the President shall, in

the light of the requirements of national security and without

excluding other relevant factors, give consideration to domestic

production needed for projected national defense requirements, the

capacity of domestic industries to meet such requirements, existing

and anticipated availabilities of the human resources, products, raw

materials, and other supplies and services essential to the national

defense, the requirements of growth of such industries and such

supplies and services including the investment, exploration, and

development necessary to assure such growth, and the importation of

goods in terms of their quantities, availabilities, character, and use

as those affect such industries and the capacity of the United States

to meet national security requirements. In the administration of this

section, the Secretary and the President shall further recognize the

close relation of the economic welfare of the Nation to our national

security, and shall take into consideration the impact of foreign

competition on the economic welfare of individual domestic industries;

and any substantial unemployment, decrease in revenues of government,

loss of skills or investment, or other serious effects resulting from

the displacement of any domestic products by excessive imports shall

be considered, without excluding other factors, in determining whether

such weakening of our internal economy may impair the national

security.

(d) [sic] Report by Secretary of Commerce

(1)Upon the disposition of each request, application, or motion under

subsection (b), the Secretary shall submit to the Congress, and

publish in the Federal Register, a report on such disposition.

The legislative veto provisions of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act

This statutory section also contains a subsection (f), set forth below, which creates a legislative veto of the President's decision to invoke the case. But it is unconstitutional.

This legislative veto provision was a feature of dozens of

statutes enacted by the United States federal government between

approximately 1930 and 1980, until held unconstitutional by the U.S.

Supreme Court in INS v. Chadha, [462 U.S. 919] (1983).

So, subsection (f) is now clearly unconstitutional, although many Presidential administrations have honored legislative veto provisions in existing laws anyway. Subsection (f) of 19 U.S.C. § 1862 says:

(f)Congressional disapproval of Presidential adjustment of imports of

petroleum or petroleum products; disapproval resolution

(1) An action taken by the President under subsection (c) to adjust

imports of petroleum or petroleum products shall cease to have force

and effect upon the enactment of a disapproval resolution, provided

for in paragraph (2), relating to that action.

(2)(A)This paragraph is enacted by the Congress—

(i) as an exercise of the rulemaking power of the House of

Representatives and the Senate, respectively, and as such is deemed a

part of the rules of each House, respectively, but applicable only

with respect to the procedures to be followed in that House in the

case of disapproval resolutions and such procedures supersede other

rules only to the extent that they are inconsistent therewith; and

(ii) with the full recognition of the constitutional right of either

House to change the rules (so far as relating to the procedure of that

House) at any time, in the same manner, and to the same extent as any

other rule of that House.

(B)For purposes of this subsection, the term “disapproval resolution”

means only a joint resolution of either House of Congress the matter

after the resolving clause of which is as follows: “That the Congress

disapproves the action taken under section 232 of the Trade Expansion

Act of 1962 with respect to petroleum imports under ______ dated

______.”, the first blank space being filled with the number of the proclamation, Executive order, or other Executive act issued under the

authority of subsection (c) of this section for purposes of adjusting

imports of petroleum or petroleum products and the second blank being

filled with the appropriate date.

(C)(i)All disapproval resolutions introduced in the House of

Representatives shall be referred to the Committee on Ways and Means

and all disapproval resolutions introduced in the Senate shall be

referred to the Committee on Finance.

(ii) No amendment to a disapproval resolution shall be in order in

either the House of Representatives or the Senate, and no motion to

suspend the application of this clause shall be in order in either

House nor shall it be in order in either House for the Presiding

Officer to entertain a request to suspend the application of this

clause by unanimous consent.

The fact that the act originally contained a legislative veto which was later held unconstitutional could be relevant to constitutional non-delegation doctrine analysis of the Act because Congress didn't intend to fully delegate this authority in the first place, and might not have done so without the added protection of a legislative veto.

CRS references:

85: Severstal Export GMBH v. United States, No. 18-00057, 2018 WL 1705298, at *8 (Ct. Int'l Trade Apr. 5, 2018).

86: Id. (citing Dalton, 511 U.S. at 474).

87: Severstal, 2018 WL 1705298 at *7 (quoting Corus Group, 352 F.3d at 1359).