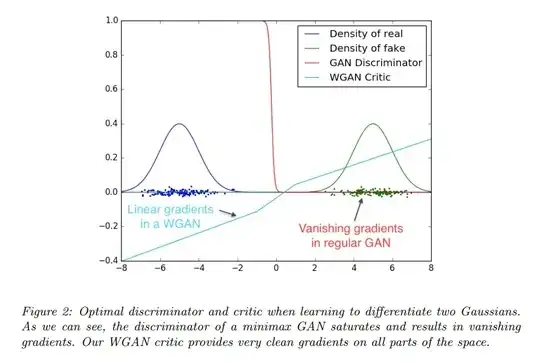

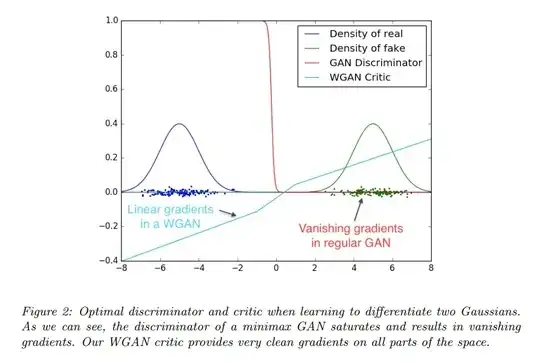

If you start with perpect discriminator, loss function will be saturated, and gradient of loss will be very small, so feedback for the generator also will be small, and learning will be slow down as a result. Actually, it is allways desired for discriminator and generator to learn balancedly. Additionally, it is claimed that Wasserstein Loss take care of this problem.

You can find more information in this article. (I strongly suggest to read)

Also from the paper " Towards principled methods for training generative adversarial networks":

In theory, one would expect therefore that we would first train the discriminator as close as we can to optimality (so the

cost function on $\theta$ better approximates the JSD), and then do gradient steps on $\theta$, alternating these

two things. However, this doesn’t work. In practice, as the discriminator gets better, the updates

to the generator get consistently worse. The original GAN paper argued that this issue arose from

saturation, and switched to another similar cost function that doesn’t have this problem. However,

even with this new cost function, updates tend to get worse and optimization gets massively unstable.

Note 1: $\theta$ is parameters of generator

Note 2: JSD: Jensen–Shannon divergence. For optimal discrimantor, loss is equal to $L(D^{ \ast }, g_{\theta})= 2 JSD(P_{r}, P_{g}) - 2log(2)$

Also from the paper of Wasserstein Loss:

The fact that the EM distance is continuous and differentiable a.e. means that

we can (and should) train the critic till optimality. The argument is simple, the more we train the critic, the more reliable gradient of the Wasserstein we get, which is actually useful by the fact that Wasserstein is differentiable almost everywhere. For the JS, as the discriminator gets better the gradients get more reliable but the true gradient is 0 since the JS is locally saturated and we get vanishing gradients ... In Figure 2 we show a proof of concept of this, where we train a GAN discriminator and a WGAN critic till optimality. The discriminator learns very quickly to distinguish between fake and real, and as expected provides no reliable gradient information. The critic, however, can’t saturate, and converges to a linear function that gives remarkably clean gradients everywhere.